Head in the clouds

Blue Robinson reflects on his life as a sailor and the friends he has made and the experiences he has enjoyed along the way.

Written by Blue Robinson

27 July 2022

Just over ten years ago, we moved from the Northern Beaches suburb of Manly in Sydney to Fitzroy Falls in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales.

Manly was a great place for water sports – surfing and sailing, and I raced my singlehanded Finn dinghy out of Manly Yacht Club.

I remember a solo training sail on a Monday afternoon, with the harbour empty and a light nor’easter building in a clear sky.

I beat out through the Heads, tacked the Finn over then surfed back into the harbour entrance, lining up with a couple of swells over a shallow bank near the inside of the Heads.

Then I pumped the sheet once to lift my boat speed just a whisker above the breeze strength until the main was weightless and I could gybe with ease. I crossed the boat, remembering to lower my elbow beneath the path of the boom and, considering the next upwind, had a think about how the breeze was bending around North Head.

Pondering all that, I glanced over the side of the boat and saw a shark way, way bigger than my dinghy just underneath me, looking back up through the gin-clear water.

I’d like to think I muttered the line from Jaws, “I’m going to need a bigger boat,” but my immediate memory of that moment is a little fragmented.

Avoiding any rash moves, all training ceased for the day, I reached the club, sitting very still with the blood draining out of my face yet pounding in my ears, knowing full well the Leatherman in the pocket of my PFD simply wouldn’t cut it if the fin had taken on the Finn.

And so, moving up to the Highlands and racing on a reservoir has seen a significant contrast in the local wildlife, plus plenty of other challenges.

The boat felt different in fresh water, it didn’t track the same, and with just 5 square kilometres of water to compete on, each race lasted about an hour. The surrounding valleys and trees made work much harder in picking the breeze.

Unsurprisingly, the competition was fierce – in Lasers, another Finn, Nacra’s and a growing number of A-Class cats.

In time, encouraged by Chris Nicholson and Glenn Ashby, I acquired an A Class and then another Finn, a beautiful timber one.

I had become friends with the great sailor and Olympian Carl Ryves. I stayed at his house and drove up to see him at his Lane Cove home on the weekends, drinking tea on the balcony, sharing tales and always laughing.

Over the years I sat with Carl and listened to his life story – first as a boy, borrowing sheets of roofing tin from nearby building sites as a kid, where he and his friends would fashion simple canoes, jamming a stick in the middle and scooping up hot tar from the roads to seal the ends, then hiding them in the bushes as other kids would pinch them if they could find them.

Then, on weekends and school holidays, in a Huckleberry Finn existence during Sydney’s golden summers, drifting downwind with bed sheets spread out on skinny arms or broomsticks.

That was until these corrugated canoes capsized as the human ballast shifted, unable to keep still the way kids are, laughing as their primitive boats slowly settled then sank beneath them, to be retrieved the next day after swimming down the string line tied to a bit of wood to mark their location.

It was over tea on the veranda while recounting these times that Carl suggested that I take ownership of his timber Finn dinghy, which was suspended by heavy ropes high up under his balcony.

His home and sheds were full of boats and bits of boats, beautiful single sculls, slender oars, masts, all timber, all varnished and all with their own story.

He knew I raced a Finn, but the offer of one of his beautiful and extremely personal items was such a surprise that I refused, and so Carl smiled and said okay.

I also refused the second time he suggested this over a later pot of tea, but on the third occasion I accepted – and he was delighted.

Lowering it gently from its slings with a group of strong mates, I towed it to my home 200 kilometres away in the Southern Highlands and raced it on the reservoir on light days, reflecting that Carl had often sailed it in the afternoons at Lane Cove, something his good friend Ben Lexcen did too, just for fun.

Over tea with Carl, eventually, the talk would always come back to Benny. Ben Lexcen was Carl’s great friend, who adopted the Ryves family as a teenager to find stability after never knowing his father and his mother abandoning him to battle her own demons.

This meant Benny, who was Bob Miller back then before changing his name, was passed around from aunties and uncles to grandparents, a difficult time for a child who would have felt like a scruffy, unwanted package.

In his teens and working for the railways as an apprentice fitter and turner, Benny travelled down to Sydney, intrigued by the International Stars based at Pittwater and Hunters Hill, plus the new Flying Dutchman fleet.

He then gravitated to the Ryves household and stayed, sleeping on the lounge or out on the veranda, washing his jeans while wearing them in the shower, where he also played the harmonica because he liked the acoustics of the cubicle.

Carl’s parents nourished him both physically and mentally – mum fed him and dad had a library of technical books by Uffa Fox on lightweight planing dinghies and yacht design.

There were the past and current America’s Cup lines, plus Manfred Curry’s book Yacht Racing: The Aerodynamics of Sails and Racing Tactics, first published in Germany in 1925 then in English in 1928, with chapters on aircraft wing profiles, various sail configurations and the resistance of air and water, bendy booms and a photograph of a sheet of ice in the middle of a river, beautifully shaped by the water flow around it to give a perfect foil shape.

I have a copy of this remarkable book in front of me now, with images of a wind-tunnel chamber and measuring apparatus in Dessau, and the author’s designed jib outrigger with its correct trimming guide.

Carl credits this book with helping Benny with the theory of sailing in his early days, fascinating the young Lexcen who devoured these ideas and concepts, storing them up in his inquisitive mind until he was allowed to run free with his theories, to become what the Australia II skipper John Bertrand would call the Leonardo da Vinci of Australia.

In 1955, Carl Ryves’s father built him an International Star, constructed as a cruising boat with a hardwood keel and Oregon planking, roved together and quite heavy.

Most of the Australian boats built prior to the 1956 Olympics were all cedar-framed and significantly lighter. Carl’s boat floated about 4 inches below everyone else’s, but he raced this heavy boat, beating most of the older guys.

He called them older because Carl was about fifteen years old and really had never raced before, perhaps a couple of times as crew on a Vaucluse Junior, but remarkably little.

Recounting those days, he was very honest. “I never really knew where the wind came from, Blue. I just sort of concentrated, really, and it all seemed to come together!”

Carl blossomed, winning championships and getting noticed, eventually representing Australia at the Mexico Olympics in the Flying Dutchman class with crew Dick Sargeant in 1968, building his own boat, mast and boom with his father, and making their own sails on the lounge floor at Hunters Hill.

They sailed well in Acapulco, Mexico, but up against the might of British sailor Rodney Pattisson and the semi-professional European and Eastern block teams, Carl came fourth after the hull of their home-built boat started to come apart.

It was also over a cup of tea on his balcony that Carl suddenly became serious. His default setting was one of laughter and smiles, but not at that moment.

He gathered his thoughts and said, “Blue, I don’t know if I’ve told you this, but it seems I have dementia. It’s not good. So, there you go.”

I first noticed a hint of this when he was asked to stand and speak at an Australian Sailing Awards the previous year about the Mexico Olympics, where he began and then stopped, then started and stopped again, his account a Swiss cheese of accurate facts and silent holes.

Carl had recently visited his doctor and, driving one of his beloved Italian sports cars, had gone in to take some tests then had his car keys quietly taken from him.

Quite quickly, things began to happen. With his children close by, Carl moved into full-time medical care and, over the past two years, I would book a Zoom meeting through the staff and continue to chat with Carl.

I think he recognised me a couple of times, but I could see from his eyes he wasn’t sure who I was. His son, perhaps? No. And was Blue a person, a concept, or simply just a colour?

And so, after ten remarkable years of Carl telling me about his life, I started to tell him about his life.

The staff encouraged this, to try to help with his memory, and so with nurses sitting either side of him, over the months I spoke of Benny and the timber Finn.

I spoke of Carl winning Australian Championships with his mates, about the replica of Benny’s 1961 World Championship-winning 18-foot skiff Venom, which Carl had painstakingly built and stored in his garage to keep the memory alive as the original rotted away near oyster beds in Queensland.

Of how Benny’s Taipan and Venom designs revolutionised the 18-foot skiff class, both blisteringly fast and controversial in equal measure, not for the last time in Lexcen’s career.

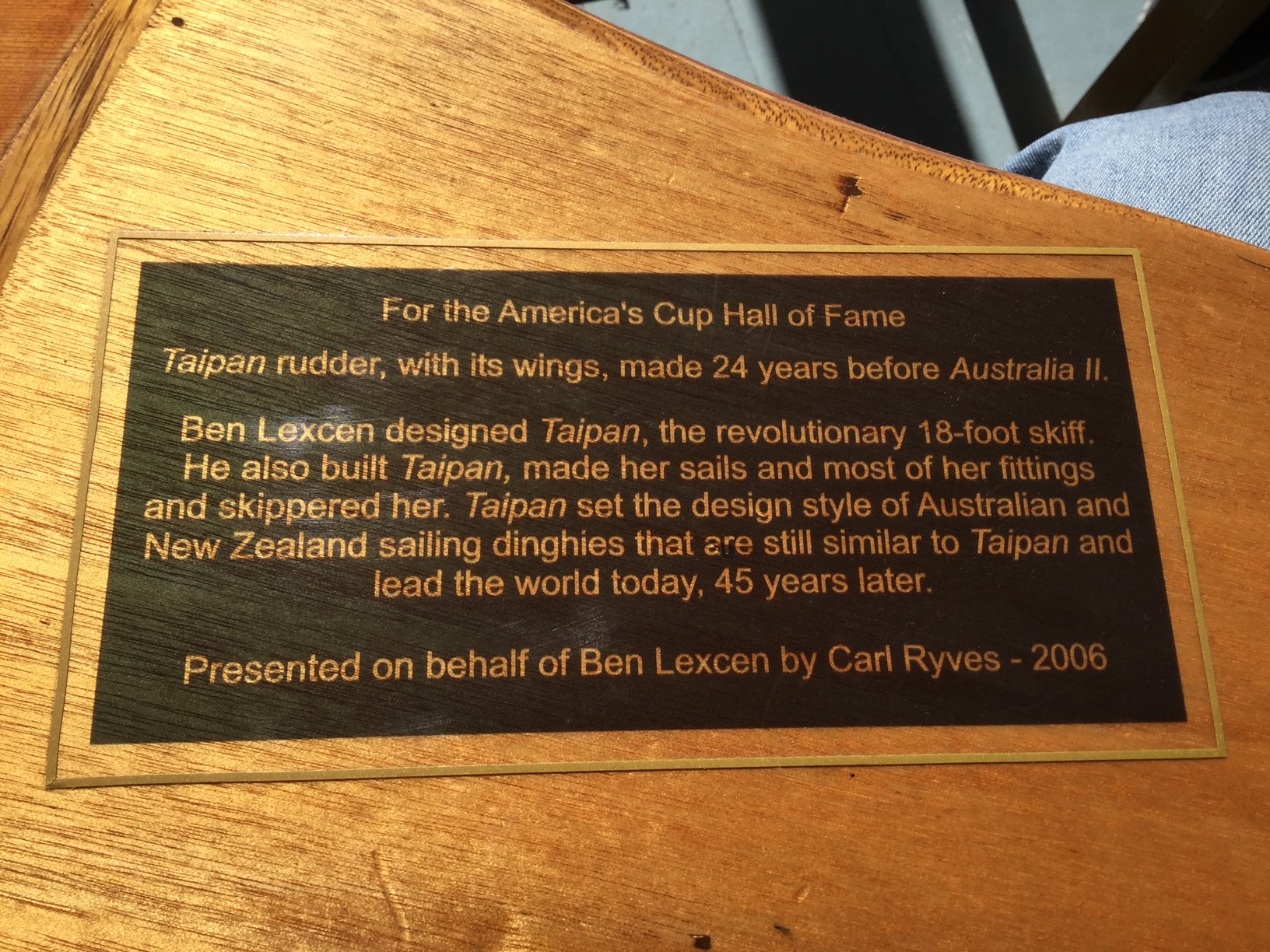

Of Carl travelling to the United States in 2006 to present the America’s Cup Hall of Fame with a replica of the rudder from the Taipan, complete with winglets that Benny was working on 24 years before Australia II.

I also spoke to Carl about him travelling to Denmark to stay with his close friend Paul Elvstrom at his home, which was stunning news to the Danish locals who regarded Paul as a bit of a hermit.

It was easy to see how Carl’s warmth and easy charm forged deep friendships all over the world.

I then spoke about how Alan Bond and Warren Jones had invited him over to Perth in 1986 to bolster their Cup defence, as part of the afterguard on Australia lll, helping its victory in the 12-Metre World Championships.

Of back as a teenager on the weekends, heading off to regattas, where they would strap their Flying Dutchman to the roof of the family’s Holden, driving up to Lake Macquarie where they often sailed all night when the breeze held in, just for the love of sailing.

All of these anecdotes over many calls were met by a slight frown from Carl, a shake of the head and a quiet, “No. Sorry. I don’t know about any of that.”

After each video call, my wife would see me shut my computer down and quietly walk out of the house, a slight eddy of sadness trailing in my wake, to walk down a track deep into the forest to help try to make sense of it all.

On our last Zoom call, Carl looked at me; polite but puzzled, simply not knowing who I was. When I asked if he remembered the Mexico Olympics, he shook his head.

“Carl, you raced against Rodney Pattison, you and Dick Sargeant, and then toward the end of the Olympics, Benny flew in to help you repair the boat.”

Carl looked at me, his frown relaxed a little and he said, quite clearly, and to the delight of the staff sitting next to him, “We got fourth – 0.7 of a point behind third place, just missing out on a bronze medal.” And he smiled.

We sold our house in the Southern Highlands last week and have returned to the coast, moving to the top left-hand corner of Jervis Bay, back to the blazing light, white sand and steady sea breezes.

There’s a sailing club there, too, but I shall miss the Reservoir Club, full of Highland farmers, mechanics, schoolteachers, vets and builders all kitted out for cold-water sailing 750 metres up in the clouds.

The locals who welcomed me ten years ago and encouraged a rules and strategy briefing from me before each race to pass on the wisdom I’ve received from Tom Whidden, Ben Ainslie, Anthony Nossiter, Chris Nicholson, Glenn Ashby, Tom Slingsby, Roger Badham and a multitude of others.

What I’ve learned through all of this is that the flickering film of life seems to be speeding up.

Those languid summers of my youth, which seemed to stretch endlessly before me, where my body seemed to know neither fatigue nor friction, running on the magic fuels of youth, which if I could bottle and sell now would make me richer than Croesus, are no longer.

I seem to be saying goodbye to friends more often now, lost through COVID or cancer or accident and, sadly, a few by their own hand.

Reflecting as I write, the lessons I have taken from all of this are, of course, to cherish the adventures while we can – both on and off the water. To laugh, smile and take the time to understand that life slips by rather quickly, and so to have fun.