A history of yachting

In every marina and harbour, there is little evidence of yachting history to be found. So, instead, we go in search of other glimpses, to gain an insight into the yachts we sail and why.

Written by John Leonida

07 June 2022

For more than 20 years, I had been a superyacht lawyer living at the heart of the superyacht industry. I advised owners, builders and superyacht designers, and was involved in some of the most extraordinary vessels to ever set sail.

And then, one warm September London morning, I was on the outside looking in – I had retired from the law but not from superyachts. My new task? To make some sense, historically, of the world I’d been working in for so long.

For several years, I’d been contemplating a post-retirement PhD. Academically, I was an economist and lawyer, but had always been drawn to history.

It had been 49 years since a nine-year-old John Leonida received the following report from my form tutor: “John is always interested in every subject and can contribute well to the lesson; is particularly interested in history.”

And so, it was time to apply my particular interest to luxury boating. Over the intervening half-century, my reading, comprehension and creative writing had improved since Miss Huntley’s judgement on my 1971 report card. I was ready.

Yet, to my surprise, there was virtually no academic work on the history of luxury yachting. There are mountains of books cataloguing the Victorian and Edwardian pursuit of elegant maritime living, but I couldn’t see the shadows of the past.

Look beyond Maldwin Drummond’s Salt-water palaces (Debrett’s Peerage, 1979), however, and there are gems to be found. In long-forgotten books and weekly yachting journals, there’s a rich and deep yachting history that is global and, arguably, goes back to the mid 19th century.

It’s a history that wasn’t the preserve of the privileged few, rather the active pursuit of many in the United Kingdom, Germany, France (the Côte d’Azur in particular), Australia and beyond.

I found an 1862 treatise on practical yachtsmanship, cruising and racing written by William Cooper, who wrote, albeit against the pomp of the British Empire:

“The great yearly increase in the number and tonnage of yachts proves that yacht sailing, the noblest of our British sports, is becoming, as it should be, the great national pastime of the great maritime nation; the magnificent fleet of vessels that now display the colours of the various royal clubs may challenge any other country in the world to produce their equal.”

For all its Union Jack fervour, there is an acknowledgement of a global yachting community and, after the flag-waving, the book has practical tips that are not so different from what you might find written in Ocean. Some chapters give instruction on commanding a yacht:

“Have a look all round, immediately after you get fairly underway, take heed that the main and pecan yards jib for how yards, and mainsheet are all coiled down ready for running or letting go: that is the whole coil of each rope is not hold down and the running part if any of them are, just capsize coil, that is turning upside down, which means you will have the running part of most, avoid the mishap of having the whole flight aloft in a tangle and perhaps blow away to leeward when it shakes loose.”

Or the chapter, Purchasing a yacht, where Cooper says of your floating home:

“Commencing your yachting career, my young friend, I would strongly recommend you use caution. Begin with a small craft, say from 5 to 8 tons, because thereby at small expense, you will be enabled to judge whether the sea and its pastime suit you, not only in a physical but in a pecuniary point of view.

“Buy, don’t build. Ships are like bricks and mortar; once you get into them, it is remarkably hard work to get out. There are plenty of small vessels suitable for the beginner always to be had. Do not bother your head about speed…

“As to appearance, a pint of paint, a pound of putty, the few particles of good taste will convert a lumbering looking shrimper into a regular Mosquito clipper… I would always prefer to examine the whole first, is not matter what may be the excellence of spars, canvas and gear, nothing to my mind will compensate for a rotten, strained or patched-up vessel.

“If she is coppered, you must examine it narrowly; will tell its own tales, unless a smart shipwright has gone down over it as the water fell, previously to your coming down, a trick which I have known to be played…”

Remember, this is 1862 and, apart from the obvious changes in technology, the advice of Cooper as to the hazards of buying a second-hand yacht are as relevant in 2022 as they were in 1862.

How many times during my legal career did I throw my hands up in horror when a client came to me having bought a yacht that was too big for their experience or pocket – and had done so without a survey!

Then, there is the fascinating yacht- broking memoir Sixty years of yachts (Hutchinson, 1950), written by Herbert E Julyan. This book proves beyond doubt there is nothing new in yachting.

After reading this anecdote-laden joy of a book, I had to downgrade many of my own unique experiences to ones that had happened, potentially, many times before I was even born.

More recently, Australia has been a lucrative market for Cantieri delle Marche’s particular brand of explorer yachts, and a week rarely goes by without yet another proposal to convert a piece of commercial tonnage into a yacht.

Similarly, Julyan recalls an 1881 meeting with the then tinplate king of America, William Bateman Leeds, who wanted to buy a trawler to convert into a yacht so he could go to sea regardless of the weather conditions. Sounds like an explorer yacht conversion project to me.

Yet, Leeds wasn’t on his own. Julyan recalls that in the late 19th century, British trawlers built of English oak were slowly being replaced with steel steam trawlers. These oak-hulled boats were magnificent at sea, widely sought after and converted into yachts with auxiliary motors.

The Leeds conversion project came in at almost £5,000 (including the initial £700 for the 21-metre trawler), which at today’s prices would be nearly £650,000 (or roughly AU$ 1.2 million).

Contemporary books like Julyan’s are not rare, but they are hiding – sometimes in libraries, sometimes in yacht clubs; occasionally they’ve been scanned, waiting to be hunted down on the internet.

Each of these insights into yachting of the past makes every yachtsman and yachtswoman reflect on their yachting experience. In a sense, there is comfort in knowing that you are part of a deeper yachting heritage that didn’t start in 2001 but goes back more than a century and a half.

Looking at the books published by The Yachtsman Library, as of 28 December 1905, they carried no less than 17 books on yacht designing and building, four on marine motor engineering, 14 on sailing and navigation, and a further 14 titles on cruising and racing history.

There is a fascinating title called Yacht etiquette: What to do and how to do it by Captain Howard Patterson (price: four shillings and ninepence, or available for a little more now as a print-on-demand title under On yacht etiquette).

Embarrassingly, when I reviewed the 2018 second edition of The law of yachts and yachting, edited by Filippo Lorenzon and Richard Coles (Informa Law from Routledge, 2012), I mistakenly heralded that book as the first and only of its type.

In so doing, I clearly overlooked A treatise on the law relating to pleasure yachts (Sweet & Maxwell, second edition 1903) written by Charles Fuhr Jemmet and Robert Berthon Preston.

Interestingly, Preston’s father was a partner of Messrs Fawcett Preston and Co, who designed and built engines for many steamships and was also an active member of the Royal Mersey and the Royal Southern Yacht Clubs, which precipitated his study of shipbuilding.

Again, that nexus between commercial shipbuilding and yachts is confirmed, and it continues to this day with yacht builders drawing on the experiences of commercial shipbuilders.

Throughout these years – as you might now be wondering – Australia is never far from the yachting world.

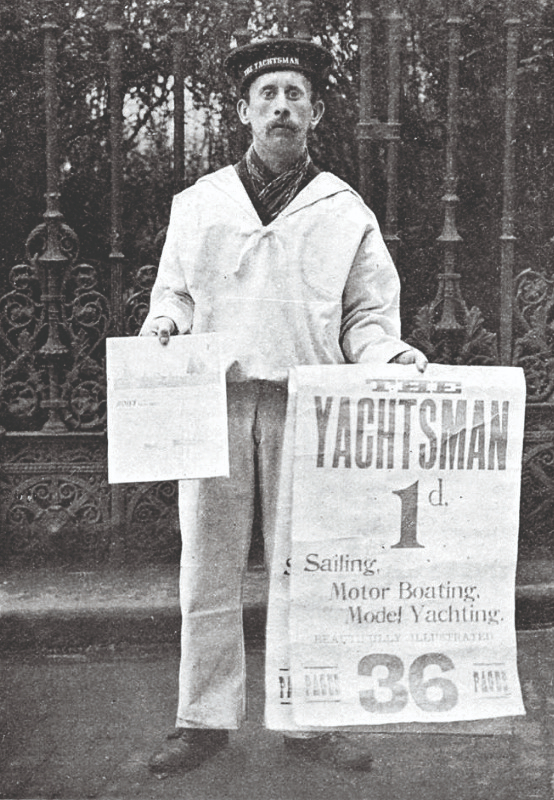

Not so long ago, the Association of Yachting Historians made available a scan of The yachtsman for the years 1891 to 1939 – over 38,000 pages of sailing and motor yachting ephemera from a golden age of yachting, which contained dozens of rabbit holes to disappear down (available at yachtinghistorians.org/the-yachtsman).

Of the 91 volumes in this digital collection, which are searchable, there are beautiful black and white photographs of cruising yachts and racing yachts under full sail. There’s a gradual acceptance of first the steam yacht and then the motor yacht as part of the yachting scene.

The magazine also mentions in December 1891 that a yacht to the design of GL Watson was being built by Messrs Scott and Co of Greenock for Mr Hordern of Sydney.

The yacht was to be taken to Australia from London on the deck of a large liner. Whereafter, as The yachtsman reports, “At the Antipodes, she will have to meet, amongst others, a 21⁄2 Rater designed by Mr Fife – the battles between the two should provide most interest in the sport for our colonial cousins.”

The magazine also reports in the same issue that an 80-tonne steam yacht was being built in Australia under the direction of yacht builders on the River Clyde in Scotland, who were to send out to Australia machinery and outfitting.

Going back to 1892, The yachtsman reported that open boat sailing was in Sydney Harbour a longstanding and very popular activity.

“It has of late years reached a high state of perfection, not only with regard to the design and building, but also in the handling. It is hardly to be wondered at, seeing the special opportunities offered by the famed harbour for the prevailing type of boat.

“There being several well-established sailing clubs, sport does not flag, and on Saturday afternoons, there is generally one and at times three or four matches from the many classes.”

On 27 January 1898, The yachtsman reported excitedly of the impending competition between Mr Garrard’s William Fife-designed Sayonara (Royal Yacht Squadron of Victoria) and the William Fife-designed Alexa owned by a Mr Belt. Yachting heritage runs deep in Australia.

Later, on 31 March 1898, The yachtsman observed the keenness that Australians showed toward yachting, noting that there had been in the Australian summer of 1897/98, good sport at the many yacht clubs across Australia from Sydney to Melbourne and from Mornington to Queenscliff and Geelong.

The yachtsman carried on 1 December 1892 an account of a voyage from Antwerp to Australia, the writer witnessing on his arrival in Australia “a brilliant display of the aurora australis, the heavens growing resplendent with long streamers of rose- coloured golden flame, feeding gradually into the soft luxuriant moonlight of a southern night.”

Indeed, there cannot be a yachtie in Australia who in 2022 wouldn’t like to prop up a bar somewhere and talk about their encounters at sea with the aurora australis.

Next time you’re gazing across a marina heavy with shiny new sailing and motor yachts, just think that perhaps 150 years ago, there was someone just like you looking at the yachts in the harbour – the difference is, they were making the shadows we look at today.