To boldly go

As the saying goes, ‘Below 40 degrees latitude, there is no law. Below 50 degrees, there is no God.’ American boater Paul Hawran recounts the trip of a lifetime from San Diego to Cape Horn and back.

17 August 2018

Rounding Cape Horn is known as the supreme test of seamanship; that is where extremes of mother nature can be found. The area’s changing nature, its beauty, splendour, and viciousness, are things few really experience.

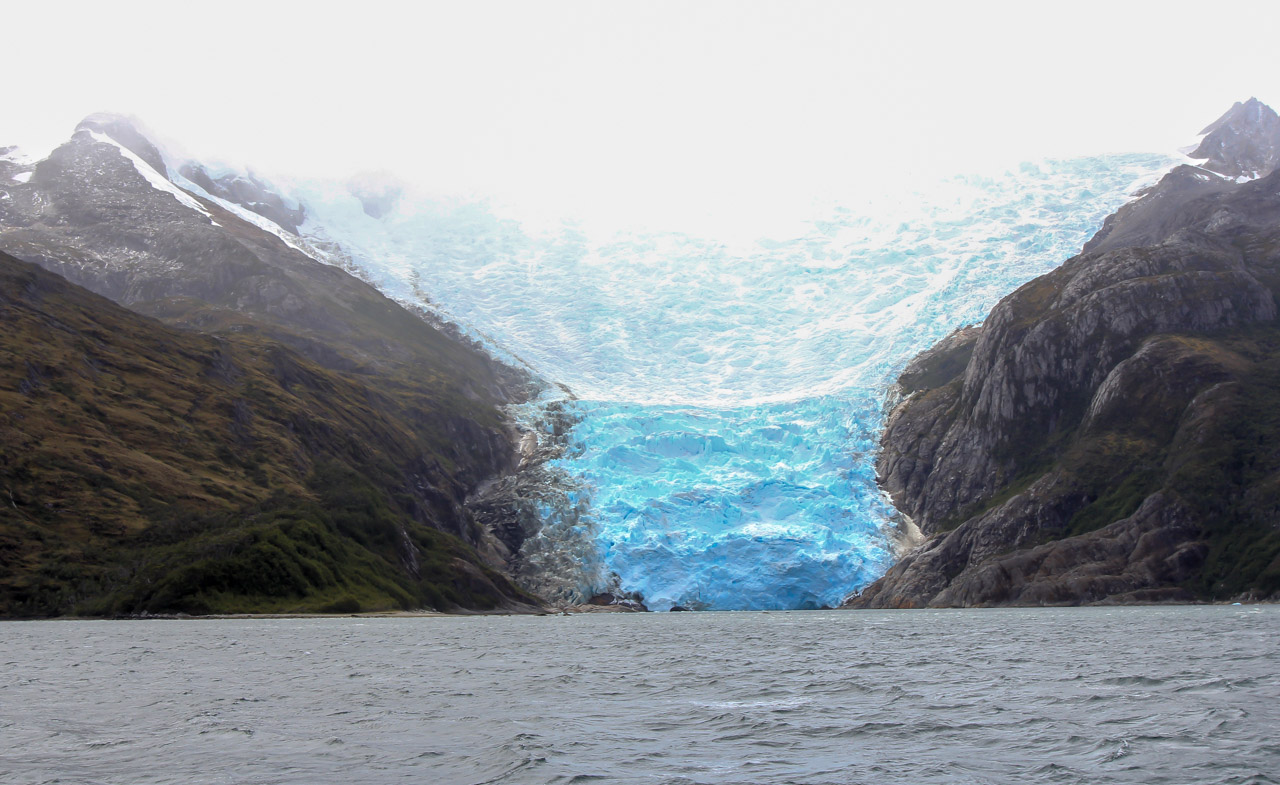

As it happens, it was also a near-lifelong ambition for me. I first started dreaming about it on an 18-hour business flight in the early 2000s when I picked up a book on Patagonia. I was amazed at the history and remoteness of the southern end of South America, but also the varying topography and nature of the region. In a very short distance, you can move from remote deserts to beautiful green and lush forests; from glaciers and mountains to barren (and I mean really barren) land.

The challenge, as I saw it, was to take my own hull and really experience the magnificence of this part of the world – you just can’t do that with a cruise ship.

Now, this is not something that I think anyone should attempt unprepared. I did as much research as I could about the area and its potentially lethal sea conditions. In terms of experience, I’ve always captained my own boats. I hold a 100-ton USCG License, an STCW, a Radio Operator’s License and I’m endorsed for radar and towing.

I’ve always felt having the credentials is a good way of making sure that I know the regulations and basics of seamanship. That said, I would never compare myself with the true mariners of the world, who have my highest respect and admiration.

I settled on an Outer Reef after a lot of research; 13 years in fact. I had already examined and researched many options, become a pain in the side of many builders and surveyors, and did a heck of a lot of sea trials. Frankly, there isn’t a boat like an Outer Reef; there is nothing more stable, comfortable or oceangoing.

Setting off

The journey really began when my Outer Reef 880 M/Y Argo was commissioned, in March 2015 in Victoria, Canada.

After a shakedown cruise to Alaska, in February 2016, I set off from San Diego for the Sea of Cortez. Although I had spent more than 20 years in San Diego, I wasn’t familiar with the Sea of Cortez and wanted to spend time just exploring and cruising.

After cruising La Paz, Cabo San Lucas, Mazatlán, Manzanillo and Puerto Vallarta, in September 2016 there wasn’t a system or sound on Argo that was foreign to me. I finally set off cruising toward South America, to be joined for various parts of the mission by my friend Mike Shaughnessy, my brother-in-law Andrew Ulitsky, my nephew, wife and son, and Jeff Druek, the owner of Outer Reef, who joined us a week before we ventured around Cape Horn.

Argo was perfect for the voyage. The sturdiness of the hull, but also the mechanical and electronic outfitting, were of paramount importance on board. And when it came to redundancy, Argo was specifically built with the saying, ‘Two is one and one is none.’ You’d be hard pressed to find a piece of electronics that doesn’t have a backup.

Prior to leaving San Diego, I put nearly US$75,000 of spare parts on board: pumps, injectors, filters, starters, and impellers.Anything that could break and be repaired was stowed on board, along with my dive compressor, fishing gear, jet ski and kayak. Even with all this planning, there were times when I needed parts flown down from the United States. Outer Reef was there to help me throughout the voyage.

Watching over us

In certain parts of Patagonia, days would pass and we wouldn’t see anyone. The Chilean Navy required that we report in twice a day. At first I was put off by the idea that I needed to report my position, but came to love the idea that someone was actually watching out for us. The regulations in South America are weird, but you grow accustomed to it, and the bureaucrats try to help as much as they can.

When it comes to the challenges I faced, I think being a spoiled US boater was my biggest. I started my venture thinking that I had done the research and knew what to expect. WRONG.

South American countries are not into yachting. There are no marinas, forget about shore power, and expect everything to cost a you a lot if you need to bring it in from the United States. That said, the people are absolutely wonderful. Everyone was helpful, accommodating, and treated us like family.

Infinite splendour

Every city, every destination I visited along the way offered an experience unlike anywhere else, often something unexpected. Even when we took a plane to the northern deserts of Chile, I was stunned. I lived in San Diego, so I’ve seen and hiked in deserts, but this stuff was unreal.

Whether it was the wine country near Santiago, the German influence in Valdivia (with better beer than I’d had at Oktoberfest), the small villages in northern Patagonia, the stark landscapes down south or the wonderful people virtually everywhere, I wish I could find words for the beauty and serenity I saw.

The treacherous Golfo de Penas was one of the more complicated passages. There is no period during the year that the area is predictable weather-wise. From the very start, I had a weather router watching our position and providing real-time advice – advice I can happily say I adhered to.

I only questioned the weather router’s judgement once – never again. We were in 80-knot winds, pounded by 20- to 30-foot waves, being pushed around at anchor. We literally bent our anchor whale. The winds over the Andean Mountains are unforgiving and if you’re not prepared for sudden gusts, you can easily find yourself in trouble. That far south, nothing beats having a satellite phone and calling your weather routers.

The ultimate challenge

Just one day before we arrived at the Cape (I can say the Cape with a certain smugness now that I’ve done it), the winds were 175 miles per hour. On the day of my arrival, the winds were a mild 30 gusting to 50 knots. The Atlantic and Pacific Oceans meet at the Cape, and frankly anyone who thinks they are a successful mariner gains a quick dose of humble pie on arrival.

The many memorials, and especially the Chapel on the Cape, show the insignificance of man when compared to mother nature.

Personally, I’m most comfortable and at peace when I’m at sea. Even in nasty situations, when stuff breaks down, I’m okay. But the evening before reaching the Cape I was filled with the gamut of emotions – anxiety about the trip, relief we were nearly there, and excitement at going where few boaters do. My feelings upon arrival can be summed up as a full-body numbness.

As you can imagine, with the intense winds and seas, the Cape itself is barren with very little vegetation. Once you climb onto the rock, you get a deep appreciation of the power of mother nature. I was reminded of the advice of other mariners: “Do your business and get the hell out of there.”

After hearing the horror stories of ships sinking, I didn’t want to become another statistic, so we left the Cape and headed back to the safe waters of Port Williams.

Argo has been through 80-knot winds, hours of pounding seas, and she is as solid now as the day she came out of the factory. The design of the keel is what makes her so steady and reliable. Although I have 12-square-foot stabilisers, there were so many times I didn’t use them; she’s just that firm. I couldn’t have asked for a better vessel in which to venture.

If I could give advice to someone considering this kind of journey, I’d say: just do it! Don’t go into it with any preconceived ideas or notions. Be open-minded, sit back and enjoy the ride. You will find wonders of nature that few boaters will ever see.

the insignificance of man when compared to mother nature. Personally, I’m most comfortable and at peace when I’m at sea. Even in nasty situations, when stuff breaks down, I’m okay. But the evening before reaching the Cape I was filled with the gamut of emotions – anxiety about the trip, relief we were nearly there, and excitement at going where few boaters do. My feelings upon arrival can be summed up as a full-body numbness.

As you can imagine, with the intense winds and seas, the Cape itself is barren with very little vegetation. Once you climb onto the rock, you get a deep appreciation of the power of mother nature. I was reminded of the advice of other mariners: “Do your business and get the hell out of there.” After hearing the horror stories of ships sinking, I didn’t want to become another statistic, so we left the Cape and headed back to the safe waters of Port Williams. Argo has been through 80-knot winds, hours of pounding seas, and she is as solid now as the day she came out of the factory.

The design of the keel is what makes her so steady and reliable. Although I have 12-square-foot stabilisers, there were so many times I didn’t use them; she’s just that firm. I couldn’t have asked for a better vessel in which to venture.

If I could give advice to someone considering this kind of journey, I’d say: just do it! Don’t go into it with any preconceived ideas or notions. Be open-minded, sit back and enjoy the ride. You will find wonders of nature that few boaters will ever see.