Time machines

The new monohull design for the next America’s Cup has received a mixed reception. But the brains behind the concept have created a hullform offering the most exciting spectator experience while drawing us back to the original concept of the competition.

Written by Ivor Wilkins

20 February 2018

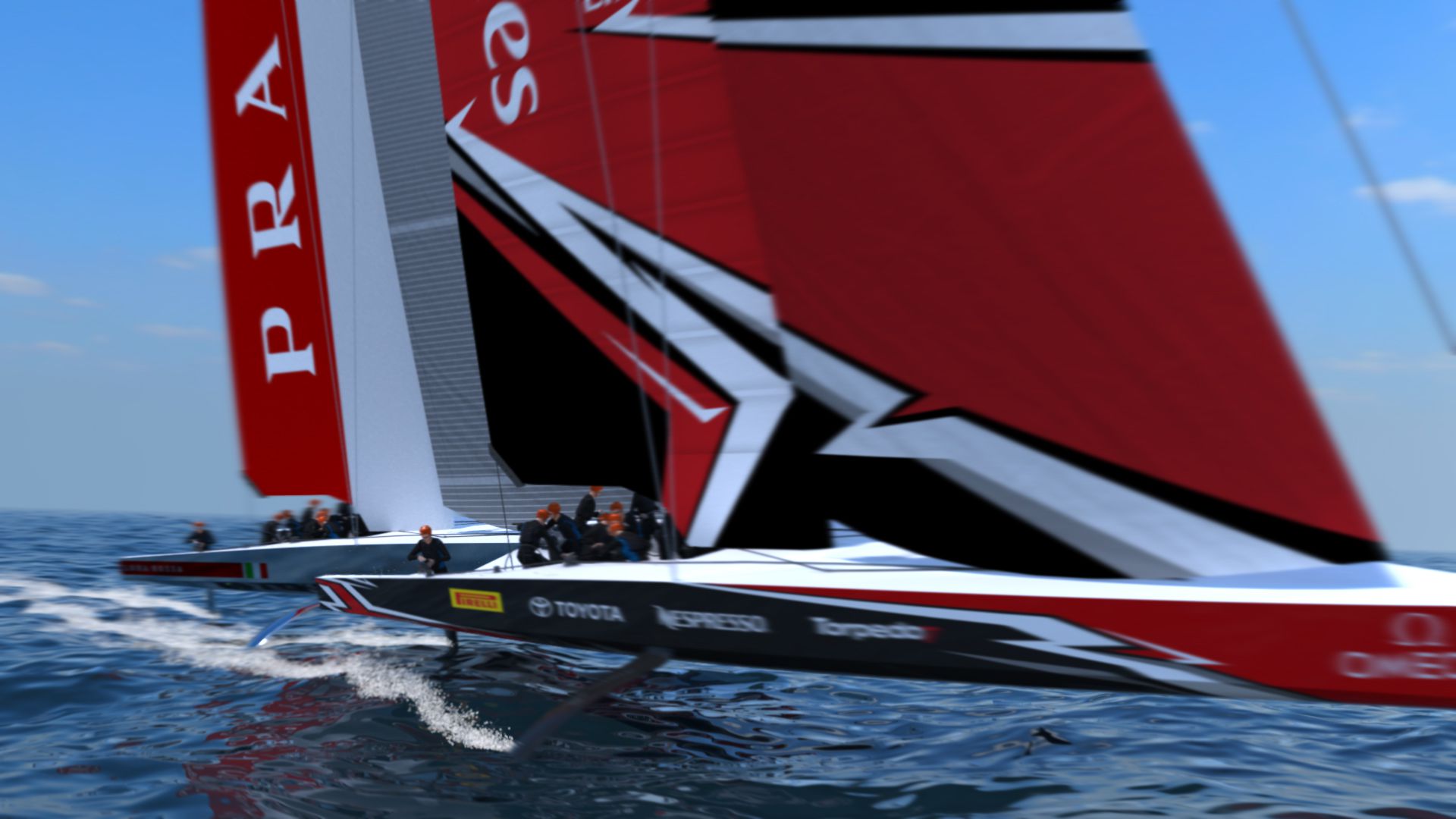

As soon as Emirates Team New Zealand (ETNZ) and Luna Rossa unveiled the concept design for the 36th America’s Cup, popular culture via the Twittersphere quickly likened the foiling monohull to the high-stepping Jesus Christ lizard, with its uncanny ability to run across water.

Inside the design team that developed the concept, several codenames were suggested, before it finally settled on something less wacky. Dan Bernasconi, ETNZ’s Technical Director, declines to reveal all the names that were proposed, but ‘DeLorean’ was the final choice.

“It obviously references the gullwing doors, but also the Back to the Future connection,” says Dan. The sci-fi movie franchise features a time machine based on the futuristic DeLorean DMC-12 car, which was described as a device “to change the past for the better”.

This is certainly appropriate for a team which, in conjunction with Challenger of Record Luna Rossa, has undertaken a kind of back-to-the-future mission to reframe the Protocol to better align with the Deed of Gift and produce a boat and sailing style with which more grassroots sailing fans can identify.

Initial responses involved a lot of “what the heck” head scratching over the radical concept and much concern about potential cost. Of course, some were sceptical, but there was also a lot of admiration for the novelty and elegance of the thinking behind it.

Mick Cookson, who has built America’s Cup boats from the IACC era through to the multihull era and many other grand prix racers besides, was blown away: “When we first heard talk of going back to monohulls, we all thought, ‘Oh, that could be dull.’ Then they come up with a solution like this and you just have to shake your head. It is brilliant. When I saw it, I said, ‘Oh man, that is so simple and clever.’ I wish I had thought of it.”

Another admirer is Cup veteran Chris Dickson. “Absolutely incredible,” he enthuses. “I thought the AC50s would be a hard act to follow but what they have come up with is a fantastic boat; incredibly innovative.”

Others, though, have expressed serious misgivings, including one seasoned Cup boatbuilder, who predicted the cost and complexity would be a major obstacle.

When the concept was launched, Bernasconi was in London with ETNZ’s Managing Director Grant Dalton and Skipper Glenn Ashby, first finalising details with Luna Rossa and then doing a presentation to Ben Ainslie Racing, the New York Yacht Club and Artemis. Guillaume Verdier was also part of the presentation team. Subsequently, Luna Rossa made a separate presentation to potential challenger groups from Italy.

“The response has been mostly positive,” Bernasconi says. “It is always exciting to see what the reaction will be when you have been working on something for months behind closed doors.”

Naturally it is rewarding to hear the positive feedback, but what about the doubters? Bernasconi responds with quiet confidence: “We are backing our work. We have done more work on the concept than anybody else, so we are confident we understand it best. Nothing has come up in the public discussion that we have not already identified and debated. Nothing has made us worry that we need to go back to the drawing board.”

That is not to say the design group is now sitting back with their feet up. In a sense, arriving at the concept was the easy part. Now the group has to nut out the details and draw up a rule robust enough to withstand multiple assaults from the best brains in the business.

This involves a switch in roles, from gamekeeper to poacher. “As the Defender, obviously we have to try to anticipate every possible angle, and both [we and] Luna Rossa will be trying to identify and close any loopholes in what we are writing. That will involve not only taking feedback from inside our own groups, but also consulting with other teams.

“Then, once the rule is written, we have to be really careful that we do not just stick to what we intended and ignore the possibilities that exist in what it actually says. We have to turn from gamekeeper mode back to poacher mode, to make sure we extract the maximum performance potential from the rule.”

As with every Cup cycle, time is of the essence and concern has been expressed that the schedule is compressed. Finalising the rule by 31 March is a challenge in itself and then the teams have a year to conduct their design work and have their first boat ready to launch by 1 April 2019.

But Bernasconi points out that it is a fairly typical timeframe, offering about six months of research and design work before construction begins. The design process always continues right through the build and beyond.

Coming up with the DeLorean concept involved a group of eight to 10 people from ETNZ and Luna Rossa, he adds:

“We started pretty much straight after the victory parades (in July), which left us sick with flu for a week from the rain and cold of New Zealand after the warmth of Bermuda.

“The initial approach was old fashioned methods of yacht design, sketching ideas, looking at weight, doing performance modelling and simulations. Our default was a relatively conventional, albeit high performance, monohull, something like a Maxi 72, but lighter.

“We had that displacement monohull concept at one end of the scale and a foiling Moth at the other. We fairly quickly concluded that the Moth concept doesn’t work at large scale, where the crew weight is a small proportion of the overall boat weight. Also, the logistics would be difficult. Just keeping it upright at the dock would be a challenge for a start, as would the transition from in the water to flight mode.

“Then there were options in the middle; more foil-assisted monohulls, like the IMOCA boats. We concluded that they are generally really only suited to reaching courses. Any foil assist system does not make you quicker upwind and mostly it makes you slower, because you have a foil sticking out [of] the side of the hull, which is not a good hydrodynamic shape when you are not going fast enough to get lift-off.

“You end up with a boat that is faster than a conventional monohull downwind and reaching, but slower upwind. From a match racing point of view, that is not ideal because it just exaggerates the amount of time you spend upwind compared with downwind.

“To have a foiling boat that is good for match racing, it needed to be foiling upwind almost as soon as downwind. So that meant it came down to a decision between a displacement boat or a foiling boat, with the middle candidates all eliminated.

“At that point, it was a question of whether we could find a concept that works for a large yacht and would be efficient enough to foil upwind and perform foiling tacks and gybes. Again, if you can’t achieve fast manoeuvres, the racing would be boring, because the teams would just hit the boundaries. For good match racing, you need to be able to do tacks and gybes without significant loss.”

The DeLorean concept emerged about halfway through the process and quickly gained momentum.

“We came up with a number of alternatives and nothing really came close. Then it was a case of developing more detail in terms of weight, the hydrodynamics, the logistics of foil control and the aerodynamic package that made us confident it would deliver the kind of performance we were looking for.”

When something so far out of left field is presented, it always begs the question, how much more outlandish were the candidates that did not make the cut?

Bernasconi shakes his head: “Actually, this was about the most extreme option. It is the most elegant fully-foiling solution we came up with. The only thing more extreme was the Moth concept, but that just wasn’t going to work.”

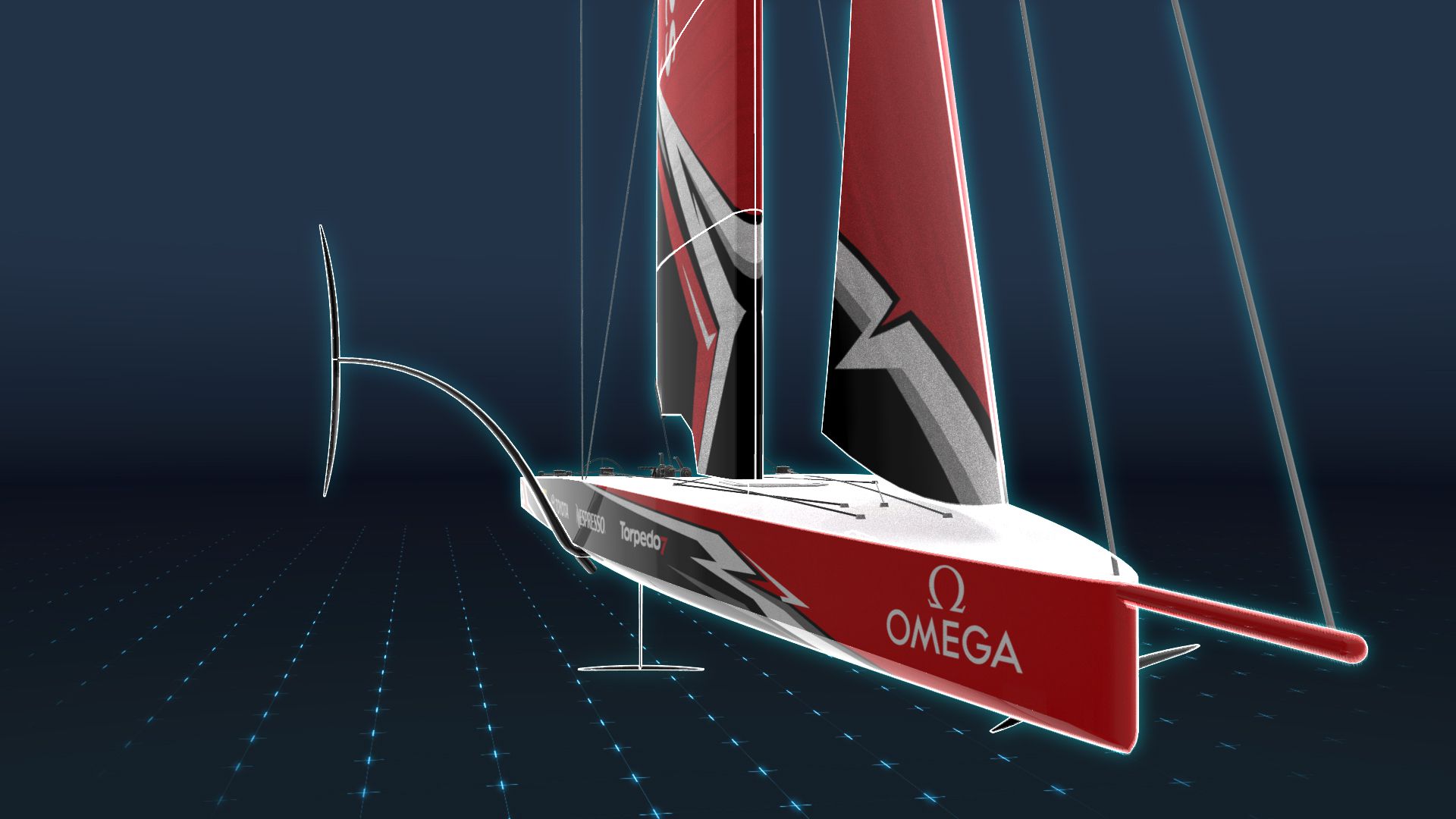

By now, the major features have been well traversed, with a caveat that the detail is still to be finally resolved. The foils protruding from each side of the hull will be ballasted and will each weigh in the order of 1.5 tonnes.

It is likely they will rotate in a single up-down plane from a fixed hull junction, with the ride height controlled by ailerons on the trailing edge of the T-wings. The main foils will be controlled by electric motors driving hydraulic pumps, although the possibility of an all-electric system is also under investigation. Cyclors and internal combustion engines will be outlawed.

Pitch control will likely be from a single, fixed rudder with trim tabs on the trailing edge of the wings, although a rake control or a combination of both are still possibilities.

The expectation is that the boats will foil in nine knots of breeze and be capable of racing up to 25 knots. From simulations, speeds will be close to the AC50s and, in some conditions, faster. Displacement will be about seven tonnes. In displacement mode, the boats will be about as tender as a TP52, but with a much bigger rig.

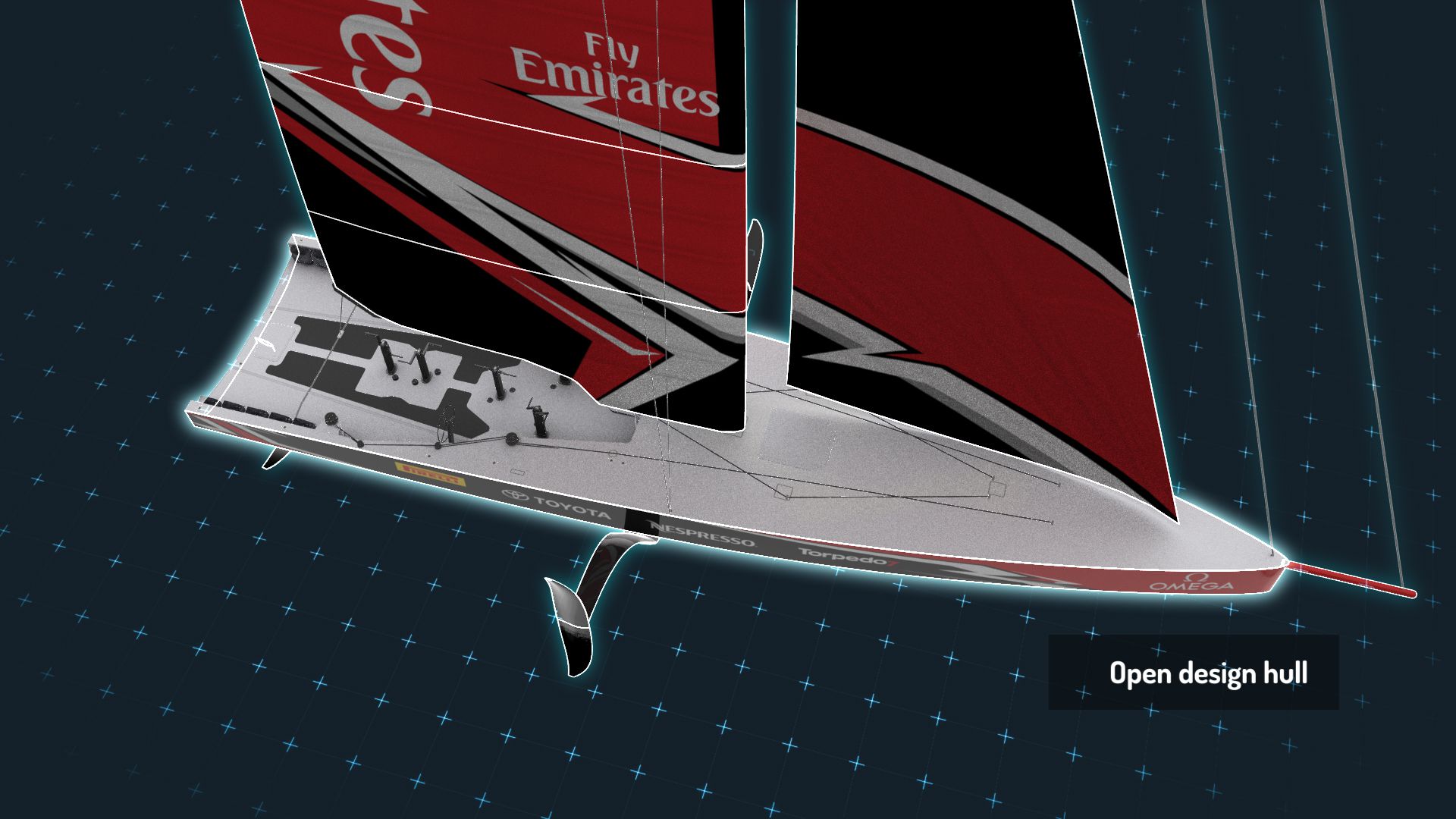

“In light airs, they will still be exciting boats to sail and it will take a huge amount of skill to sail them through the transition to foiling, which also poses an interesting hull design challenge,” explains Bernasconi. Hence, while there will be considerable areas of one-design to contain cost, the hull will be an open design.

“The hull shape is a significant area of development,” he adds. “Luna Rossa and [ETNZ] both wanted to bring the relevance of hull design back into the Cup. A big part of the design race will be about who can get on their foils first and who can accelerate fastest.”

Automation of the flight control, artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies will be heavily constrained.

“We want sailors, not computers, sailing the boat. The rules will be drafted to achieve that as much as we can. It is quite difficult to construct rules that allow enough freedom for innovation but still require sailors to sail the boat. In the last Cup, the rules were written to exclude autopilots, for example. But teams found a way around that by effectively having an autopilot tell the sailors exactly what to do. The computer was heavily involved in maintaining the flight stability of the boat.”

The draft, with both foils down in docking mode, will be no greater than five metres. The rig is still under development but will feature soft sails, including code zeros for downwind legs. The mainsail concept is likely to involve a twin-luff set-up, which creates a much more efficient wing-like transition from the mast to the sail.

“The other advantage is that a wing-type topology allows you to more accurately control twist and camber along the length of the spar. Something the AC50s developed was control where the top of the wing was loaded in the opposite direction to the rest of the wing. This meant that when you wanted to depower in higher wind conditions, the top of the wing could work in opposition to the bottom, which provided more drive force for the same roll moment.”

With the foils protruding from the sides of the boats, they have been compared with medieval chariots that have swords spinning from the wheels. Bernasconi acknowledges the safety issue but says it is not much different in reality from a multihull. The solution is likely to be a diamond-shaped electronic virtual boundary protecting the flanks. This will be visible to the helmsman, umpires and TV audiences on a display and penalties will be imposed for any penetration of the virtual zone. Bernasconi says this was already discussed with the AC50s.

“We want to have good, aggressive match racing but we don’t want collisions; no good result ever comes from a collision. With the virtual contact zone, you can still push aggressively and put penalties on your opponent without that resulting in a physical collision. When you are talking about the boat speeds involved, that makes sense.”

As to concerns about cost, ETNZ has long experienced a struggle against big-budget rivals and says it is committed to containing costs where possible with one-design elements, banning tank and wind-tunnel testing, limiting two-boat testing and allowing teams to share designs.

“We are acutely aware of the importance of keeping the costs manageable,” says Bernasconi. “The reality is that the America’s Cup is an expensive game and [the] teams always find ways to spend more. Even if it were a 30-foot displacement monohull, the big teams would still spend a vast amount on R&D.

“Even so, the cost of building the boat in the context of all the other expenses, particularly personnel, is a relatively small proportion of the overall campaign cost.

“It is important not to dumb it down too much. It is the America’s Cup, so you have to strike the right balance between attracting as many challengers as possible while keeping it at the pinnacle of sailing with boats that are technologically impressive and the most exciting boats to sail. We have thought pretty hard about that.”