Serious sailing luxury

Amel’s first sloop in three decades suggests it has eschewed its famed shorthanded, go-anywhere ketch cruising philosophy but, as Pip Hare discovers on a two-day trial, nothing could be further from the truth.

24 February 2022

Amel has a long-established following of liveaboard and bluewater cruisers, reputed for its singular way of doing things and famed for its ketches designed for two-handed sailing.

So, when the La Rochelle yard unveiled this Amel 50 – its first sloop since 1997, and one with a broad, modern hull shape and twin rudders – it was met with surprise.

Had Amel abandoned its heritage in favour of what’s in vogue? Fortunately not. Step aboard and you quickly understand why this is a brilliant new model, one true to the brand’s DNA but versatile enough to suit everything from coastal sailing to global cruising.

I arrived in La Rochelle, France, for my two-day live-aboard test on a dark, wet, windy and cold December morning – but with its fully enclosed doghouse, the Amel 50 was made to take on weather like this.

Setting out in a brisk westerly and lumpy seas, the heat from below decks soon flowed up the companionway to fill the doghouse.

Within minutes, we were punching our way confidently upwind, oblivious to the raging weather.

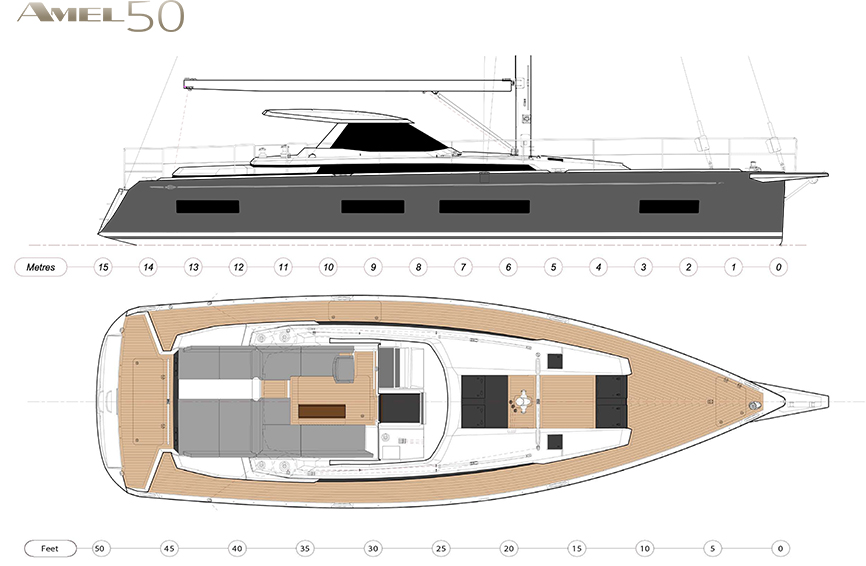

The 50s’ lines, from Berret-Racoupeau, follow modern trends with a blunt stem, full bow, high topsides, modest sheer and a beamy transom.

It’s also the yard’s first model built using resin infusion. Amel has long favoured ketch rigs in the belief that the sail plan is more manageable for couples. Ironically, this may have put off some sailors who consider two masts double the work, not half.

With the new 50, the sail area was considered small enough to be comfortably handled as a sloop. Losing the mizzen also means reduced build costs, a larger cockpit and more below-deck versatility, making the Amel 50 an attractive package.

Taking the helm, I was acutely aware of my position on the boat – at the front of a central cockpit and offset to port. Looking forward, with only half the boat ahead and a small wheel in my hands, I had the impression of sailing something much smaller.

The pillarless windscreen offers a panoramic view and the cockpit is high enough to give vision to windward, even on a starboard tack.

The mainsail can be seen through deckhead hatches, while the view of the jib luff is great on a starboard tack – straight up the slot – but more difficult on port as the forestay sags to leeward.

There’s a helm chair, but I found standing more comfortable as, when seated, my arms were at full stretch.

The steering is sensitive to movement but has little feeling as the cables don’t load up. I quickly tuned in to other performance indicators – using angle of heel particularly to guide me upwind – and immediately the helming experience came alive.

The mainsail unfurls at an impressive speed using joystick controls in front of the wheel.

The outhaul runs at the same pace on a continuous line system. To avoid damage, both use a current-sensitive, time-out feature so if either is placed under heavy load, they will momentarily stop, alerting crew to a potential sail jam or rope snag.

The jib sheets neatly through a wide shroud base and on to electric primaries, while manual secondary winches allow jib cars to be trimmed while sailing. Powered-up under full main and genoa in 18 knots of wind, we ploughed through waves at a decent 8.1 knots with a true wind angle of 50 degrees – perfectly acceptable for offshore passagemaking.

Our test boat had the optional cutter rig adding a 24-square-metre, self-tacking staysail to the 126-square-metre sail plan. Setting the staysail while beating in 20 knots added 0.3 knots with no impact on balance. I can’t imagine why you wouldn’t tick the staysail box.

It adds a manageable sail area to the forward triangle while providing a dedicated heavy-weather option. Off the breeze, we waddled a little with jib alone, but a furling gennaker scooted us across the waves at 9 knots in 20 knots true.

Helming required concentration but once again absorbed me, and I unashamedly grinned at this dry sailing experience. In the blink of an eye, the sails were away and the anchor deployed using the remote windlass controls behind the wheel. With the cockpit table extended fully and set with warm food, the transformation was complete.

Over lunch, I learned more about Amel’s ‘maximum enjoyment, minimum work’ philosophy, which not only covers sail plans but also every aspect of design and construction.

These boats are built to stand the ravages of time and the sea while incorporating details to reduce maintenance, make repairs uncomplicated, and ensure life on board is simple and safe.

Touches include a specially extruded mast section that keeps halyards, electrics and furler separate, a spy glass in the hull giving direct sight of the prop, and chafe protection at every point a locker lid might scratch the stainless-steel handrail. Back under way after lunch, we first poled out the headsail with the huge, vertically mounted jib pole, then tried the Code 0.

The white sails downwind set-up is good. There’s a welded tang mid-boom, which allows a preventer to be attached from inside the footprint of the deck, and the substantial jib pole is utterly fit for the job. Downwind performance was comfortable and efficient.

We made close to 9 knots dead downwind in 22 knots true. As the breeze died, we maintained our VMG by setting the Code 0 with the jib pole. Sailing in the sun felt heavenly and the whole crew gravitated to the aft deck, leaving the autopilot to drive.

As the light faded, we found a mooring buoy and I took the controls on approach. This didn’t prove easy at low speeds in the gusty breeze as there’s a lot of windage on the hull and superstructure. The twin rudders provide little prop wash to counteract any last-minute gusts so, on my second attempt, I resorted to the bow thruster.

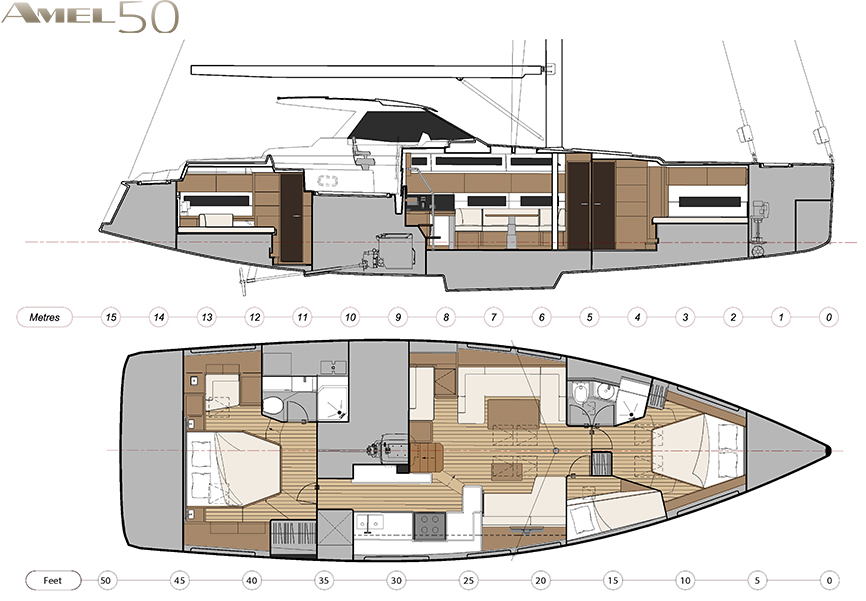

This proved equally efficient when reversing into the berth at the end of the test. The cockpit sole lifts to reveal a spacious, watertight engine room, accessed via a small ladder.

Everything is well set out with good access. As well as the 110 hp Volvo engine, the test boat housed a generator, watermaker, air conditioning unit and two inverters.

Through-hull fittings have been kept to a minimum using a single inlet and seawater manifold. All tankage is housed under the cockpit sole. Below decks, the Amel 50 is as luxurious as you’d expect for its starting price of around AU$1.67 million. The test boat finish was light oak with stainless-steel details.

There’s a feeling of space throughout, especially in the saloon, which despite the raised cabin sole has nearly 2 metres of standing headroom. Light floods in from mid-height windows in the topsides and high-level coachroof hatches.

A snug chart table nav station surrounded by switch boards is set into the aft port corner, while to starboard there’s a step down to the corridor galley. Two large sofas flank the saloon, one wrapped around the dining table to port. A couple of occasional tables can double as stools and provide all-round seating when the dining table is extended. These are anchored under the folded table while sailing.

The master cabin aft has a large island double bed, writing desk, sofa and ensuite.

Another big double in the bow shares a head and shower with a smaller bunk-bedded cabin to starboard, although the top bunk folds away to create a little more room.

All bunks have lee boards or cloths making even the island beds usable sea berths. The accommodation is separated from bow locker and lazarette by watertight bulkheads, and internal bulkheads can be made watertight thanks to special clamps and seals.

The large galley is well-equipped with a proper sink, fridge/ freezer drawers and plenty of worktop and the passageway is wide enough for two people to pass yet slim enough to brace while at sea. The head-height storage lockers feature a drawer front that slides out on tracks, keeping the contents retained when the locker is uphill while still allowing access. The sun rose on the second day to reveal flat water and light winds.

With 8 to 12 knots true wind, the Amel 50 performed with a Code 0, gennaker and downwind asymmetric, but using white sails alone proved a little slow. I’ve come to accept that poor light airs performance is the trade-off for comfort in boats of this genre, but as the breeze died, the Amel 50 just kept going. With the jib set in just 5 knots true we maintained a boat speed of 4.5 knots at a 60-degree true angle.

Blessed with perfectly flat water and a stable wind direction, this final flourish of performance only confirmed my growing admiration.