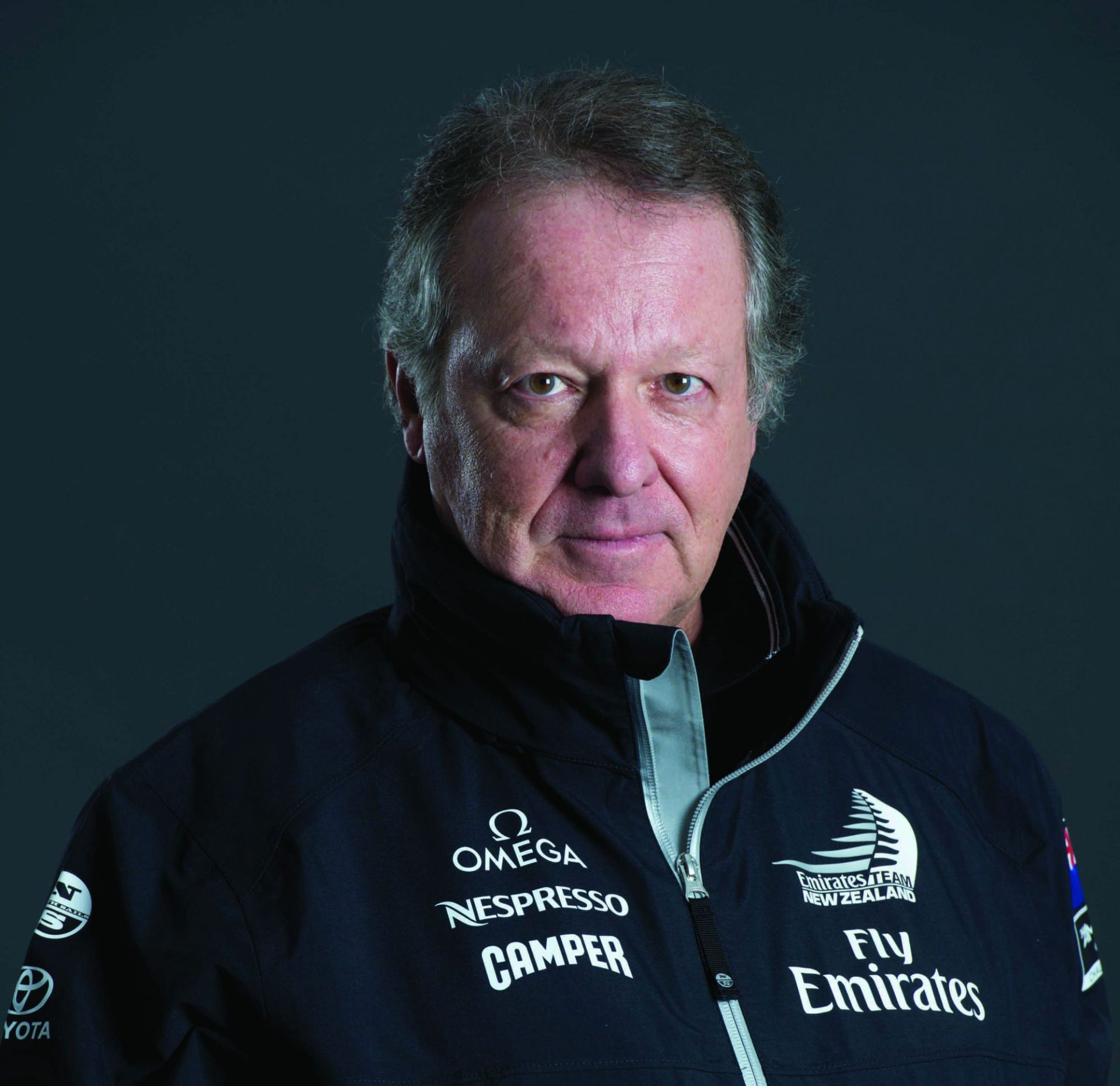

Quiet achiever

Dr. Matteo de Nora is a true renaissance man, having enjoyed unparalleled success as a businessman as well as making seismic contributions to medical science and as a philanthropist. As backer of Emirates Team New Zealand’s attempts to win the America’s Cup, however, he is a decidedly modest presence that belies his impact and expertise in the world of yachting, writes Ivor Wilkins.

Written by Ivor Wilkins

Photography by Gilles Martin-Raget

21 June 2017

Throughout its long and turbulent history, the America’s Cup has been populated by larger-than-life personalities – wealthy entrepreneurs, aristocrats and captains of industry well-versed in the cut and thrust of business and keen to direct their combative energies to win-at-all-cost battles on the water.

From the early days of the Morgans, Vanderbilts and Liptons through to the modern era with protagonists like software billionaire Larry Ellison, pharmaceuticals mogul Ernesto Bertarelli and fashion boss Patrizio Bertelli, it has been a high-stakes game driven by personal obsession. Powerful people aroused by powerful passions, and the sometimes bitter clash of these alpha personalities on and off the water has helped fuel the fascination of the Cup.

While public attention is drawn to these high-profile players, many wealthy backers have chosen a more discreet participation in the game. Dr. Matteo de Nora, who has long been a significant contributor to the New Zealand America’s Cup cause, is one example.

Quietly spoken and understated, de Nora’s modesty constantly reveals itself. At one point in our conversation, he breaks off to speak to Emirates Team New Zealand CEO Grant Dalton and then apologises for the interruption. “I am just trying to make myself look important,” he jokes at his own expense.

Multilingual de Nora has a decidedly cosmopolitan pedigree. His mother was Swiss, his father Italian; he was born in the United States and is a Canadian citizen, who lives in Monaco and regards New Zealand as his second home. Matteo’s father was a professor of physics and chemistry. The family business, founded in 1923 and based primarily in the electrochemical industry, has since grown into a multinational enterprise with diverse interests.

Matteo entered the company after an international education at the Bocconi University in Milan, one of the top-ranked business and economics universities in the world, followed by an MBA from the MIT Sloan School of Management. In more recent times, he has divested and relinquished much of his direct involvement to the next generation.

For many years, his role in New Zealand’s quest for the America’s Cup remained almost completely anonymous, known only to an inner circle. But, more recently as his support has become more obvious, he has relaxed his guard.

Unlike some of the Cup’s more fanatical devotees, he says he is not defined by it and constantly underplays his involvement. “I am not the boss of Emirates Team New Zealand and I do not make the decisions,” he says on several occasions. “What I think and say about the America’s Cup is not necessarily what ETNZ thinks.”

De Nora’s path into the team reflects the highly-integrated nature of the New Zealand marine industry – the way success in the sporting arena has fed success across the whole spectrum of boatbuilding, from race yachts and equipment to superyachts and vice versa.

Ownership of a New Zealand-built superyacht made the connection with the country, and ultimately led to his involvement with the Cup team. Designed by Dubois Naval Architects, the 33-metre sloop Imagine, built by Alloy Yachts, was launched in 1993 for Swiss banker Bernard Sabrier.

De Nora was a close friend and became a partner in the boat, later becoming the outright owner when Sabrier built the more performance-oriented Silvertip at Yachting Developments. De Nora subsequently built the 44-metre Imagine II at Alloy Yachts, which won the top prize in its category at the 2011 World Superyacht Awards.

“I did not come from a sailing family,” he says. “As a young man, I was involved in offshore powerboat racing. This was in the 1970s and ‘80s, when car engines were starting to be marinised. I was friendly with [Belgian Formula One racer] Jacky Ickx for many years. My family was indirectly involved with Ferrari and we built a car with them at one point.

“With Jacky, we used marinised Porsche engines in our race boat. When the boat went, it was incredible, unbeatable. The problem was with the early electronics, which were unreliable and suffered from all the banging and crashing in the marine environment.

“Offshore powerboat racing was a wild ride. It was very dangerous and we had our share of crashes and capsizes, but I only realise today quite how dangerous it was. How could I be so stupid? You ask yourself these questions.” He shakes his head at the follies of youth.

“Now I feel a bit ashamed that I was involved with all that noise, but it was cool at the time. It was at that moment when offshore powerboat racing was changing from a gentleman’s sport to a professional circuit.”

His later introduction to Imagine taught him that long-distance offshore cruising was better accomplished in sailing boats than powerboats. “They did not have those explorer-type motor yachts at that time.”

On his cruising excursions, he tends to shun the crowded glamour spots, where the rich and beautiful congregate. “I did not want a sailing boat just to cruise from Saint-Tropez to Porto Cervo and those places,” he says. He wanted to go around the world and is drawn to remote, off-the-beaten track locations, away from the madding crowds.

He certainly achieved that ambition. Under his ownership, Imagine completed five circumnavigations, including trips to the Arctic and Antarctic. Despite a prodigious mileage, the yacht was impeccably maintained and looked as fresh and new the day he sold it as when it was launched.

“I like to keep things and not replace them all the time,” he says of his decision to sell the dark blue sloop after more than 20 years. “But it gets to the point where updating a boat doesn’t make sense any more.” This is as much an aesthetic consideration as a pragmatic one. He argues that modernising a classic yacht undermines its integrity – which he worked so hard to maintain.

Fortunately, he was able to sell Imagine to a friend with similar values, a younger man with hotel interests, who sailed with him as a guest. In thus keeping Imagine within a close circle of friends, it continues a charmed provenance of people who learned to love it before they owned it. “I am to the new owner what Bernard Sabrier was to me.”

As de Nora’s interest in sailing and New Zealand grew, so did his interest in the America’s Cup. He was gradually drawn into supporting first Peter Blake’s Cup campaigns and then Grant Dalton’s.

His affection for New Zealand, which he calls his second home (he owns an extensive property in the Bay of Islands) has seen his philanthropy extend far beyond sailing. In 2011, he was made a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (CNZM) for his America’s Cup contribution, but also for major contributions in neurology research through the University of Auckland, with particular reference to tinnitus.

More recently, he donned a tuxedo for the first time in three decades to receive a Friend of New Zealand Award at the 2016 Kea World Class New Zealand Awards. Along with his marine and medical research activities, this also recognised significant contributions in the wake of the Christchurch earthquakes in 2011.

De Nora’s involvement with Team New Zealand ramped up considerably in its hour of greatest need after the disastrous 2003 Cup loss, when Dalton was called in to rebuild the team and New Zealand’s damaged reputation. “I would not have done it if Grant was not there.”

And, the truth is, the team would not exist today if de Nora was not there – as Dalton has publicly acknowledged on several occasions. During this interview, he re-emphasises the point. “Without Matteo, Team New Zealand would have sunk many times – in 2003, 2007, 2013.” He pauses and then continues counting, “2014, ’15, it goes on…”

For de Nora, it is an opportunity to be involved in a project that interests him. “With offshore powerboats, I had an opportunity to race with Jacky Ickx. Why would I turn down an opportunity like that? With the America’s Cup it is the same. I had an opportunity to do something with Grant Dalton, otherwise I would not have done it.”

In part, his interest is piqued by the intrinsically underdog nature of New Zealand campaigns – a small team, representing a small nation, battling some of the world’s technological giants with massive war chests. He likens it to the fairytale story of the Leicester City football team’s triumph against the odds in the English Premier League under the direction of Italian manager Claudio Ranieri.

“What is exceptional about Ranieri is that he took something that was broken and brought it back and he did it without a huge budget. Anybody can buy a successful team for $500 million and win. Ranieri is a fantastic guy. He gave the team energy and belief more than money. This is the type of story that I like.”

When de Nora stepped up his Team New Zealand involvement in 2003, it was a team similarly broken. The appeal was to help rebuild it to a point where it was competitive again and do it efficiently – not just by pouring massive amounts of money into it.

“The measure of success is not just about winning. Grant and I disagree on many things and this is one of them. He is more obsessed about winning. For me, it is about taking something that was basically non-existent and making it perform again. It depends on what stage you began at and how far you have taken it and with what means at your disposal. That is the interesting thing.

“To me, going to Valencia [in 2007] and finishing second, and the same in San Francisco, I regard it as a success, absolutely.”

Dalton, who has always been his own harshest critic, sees things in starker black and white. He shakes his head. “The team worked well. We did a good job. But we didn’t win.”

Dalton also contradicts de Nora’s modest assessment of his own contribution to the team. “He is understating it,” Dalton insists. “I listen intently to what he says. I can’t think of a time when I haven’t taken his advice. I have had two mentors in my life. Gary Paykel [of whiteware firm Fisher & Paykel who backed Dalton’s first Whitbread Round the World Race campaign] is one. The other is Matteo.”

After the San Francisco Cup in 2013, stormy times once more faced the team. Its future was precarious to say the least. Dalton recognised that changes were needed. He reshaped the design group and brought new talent into a much-reduced sailing team built around 49er aces Peter Burling and Blair Tuke with serial multihull world champion Glenn Ashby as skipper.

Dean Barker declined an offer to become performance manager and quit in high dudgeon. It was a rocky period and the first to publicly come to Dalton’s defence was de Nora, who declared 100 percent support for the embattled team boss.

“Grant is not always an easy guy,” de Nora says. “If he was a politician, he would be called a conviction politician. As such, he has some extremely loyal fans and colleagues and a lot of enemies.

“I don’t think people realise how much is involved in running an America’s Cup campaign. It is one thing to manage a sailing team. It is quite another thing to manage a campaign and not many people can do it. Russell Coutts is one. Dalton is another and I am not sure there are many more.

“You have to understand so much more than just sailing and the dynamics of the sport. It is about business and leadership and choosing the right people and motivating them and making them work together. It is above all, about making tough decisions.

“If you get seven out of 10 decisions right, you are probably on top, but nobody is perfect. We all make mistakes, but not making a decision at all is often the worst mistake. Coutts and Dalton both get the essence of what must be done to move forward. It is a tough job. I wouldn’t want to do it.”

The full feature, including de Nora’s views on the current event and what he would change if ETNZ won, can be read online http://oceanmagazine.realviewdigital.com

Satisified superyacht extends its stay