Precious vessels

We delve into the Time & Tide archives and look back at classic yachts owned by women in the gilded age of yachting.

Written by John Julian

Photography by Getty Images

31 August 2020

The barge she sat in, like a burnished throne,

Burned on the water; the poop was beaten gold,

Purple the sails, and so perfumed, that

The winds were love-sick with them, the oars were silver,

Which to the tune of flutes kept stroke, and made

The water which they beat to follow faster,

As amorous of their strokes. For her own person,

It beggared all description.

William Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra,

act 2, sc. 2, l. [199]

While it’s true that some fairly flowery language has long been part of marketing large yachts for sale and charter, Enobarbus’s description of Mark Antony’s first glimpse of Cleopatra’s barge (and its owner) might be almost too rich for a 21st-century brochure.

But, given this account, it was hardly surprising that the Roman soldier was so swiftly seduced by the Egyptian queen and the fact that she had the contemporary equivalent of a superyacht at her disposal could only have enhanced Mark Antony’s perception of her already considerable appeal.

True romance

Love stories involving yachts are not uncommon, of course. Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, the stars of the 1962 movie Cleopatra, were first photographed together away from the film set on board a boat, proving that life does indeed imitate art, and they subsequently owned the Edwardian motor yacht Kalizma during the first of their two marriages.

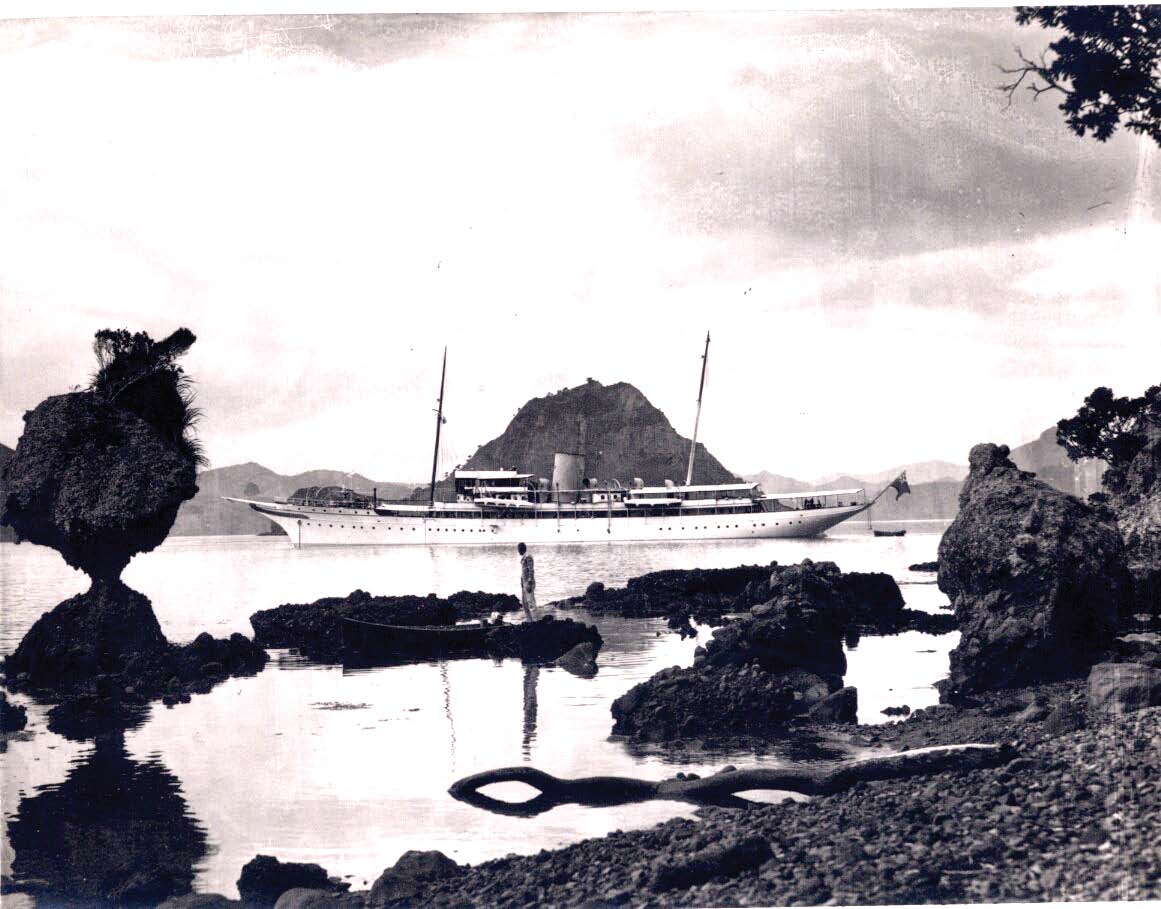

A quarter of a century before, the steam yacht Nahlin had provided the backdrop for the burgeoning romance between the man who was briefly King Edward VIII and his wife-to-be, Wallis Simpson, but the vessel itself belonged to Lady Yule, a wealthy widow of some years’ standing who was said to have been romantically linked with the Native American chief for whom the yacht was originally named.

Of the great yachts built during the Depression years, three of the most spectacular were owned by women.

Annie Henrietta Yule’s husband (and cousin) Sir David left her the staggering sum of $US100 million when he died in 1928 and she decided that, at the age of 53, she would like to sail around the world with her daughter.

Accordingly, she commissioned the 90.2-metre GL Watson-designed steam-turbine-driven Nahlin from the famous Clyde yard of John Brown and did so, visiting New Zealand during the Southern Hemisphere summer of 1934.

Nahlin was not the first big yacht to cross the Pacific with a lady owner, however, for Tom and Annie Brassey had taken their 576-tonne, composite three-masted schooner on a 35,400-nautical-mile circumnavigation sixty years before. This adventure was later described by Annie in her book A Voyage in the Sunbeam.

The other two vessels to emerge in the wake of the Wall Street crash were both built in Germany during 1930–31 for American ladies, although one was a wedding present from her husband. Neither spent much, if any, time in United States waters.

This was probably quite sensible given the severe economic hardships experienced by the vast majority of the population. Both, like Nahlin, were subsequently bought by foreign heads of state before enduring long periods of neglect, only later to be rescued and restored.

Rivalling royalty

Emily Roebling Cadwalader’s Savarona was built at Blohm & Voss in Hamburg to a Cox & Stevens design and at 136.03 metres LOA would remain the largest non-royal yacht ever built until the early years of the 21st century.

At $US4 million, she was expensive too, but Emily’s grandfather John A Roebling had been a very successful engineer with several substantial projects to his name, including the Brooklyn Bridge, and her husband Richard McCall Cadwalader came from an old and wealthy family in Philadelphia and they had owned big yachts before.

It was only after Savarona was launched in October 1931 and was preparing to leave Hamburg for Bermuda that Mrs Cadwalader became alarmed at the size of her outgoings and reduced the crew by 35 men to a paltry 72.

As it turned out, this vast private vessel became something of an embarrassment and only two years passed before she was returned to Hamburg to be laid up.

Five more years would elapse before Savarona was sold for $US1 million to the Government of Turkey which, in turn, gifted her to the President, Kemal Ataturk, who only spent six weeks aboard her before dying a few months later.

Wedding gift

While Emily Roebling Cadwalader overreached herself, the investment banker Edward F Hutton had been playing a different game. Urging the owners of big yachts to keep them in commission during the Depression, he explained that the employment generated, along with the ensuing goodwill, would outweigh any feelings of resentment toward those still able to afford these vessels.

The canny Hutton was not only being public-spirited, but he was also trying to avoid undue hostility in advance of the launch of Hussar. At 109.5 metres LOA, Hussar was the largest privately owned sailing yacht ever built. This full-rigged auxiliary four-masted barque was actually his wedding present to his wife, the General Foods heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post.

Hussar was very much Marjorie’s yacht.

She spent the two years that the vessel was in build at Krupp Germania Werft in Kiel choosing furniture and fabrics and working with a mock-up of the vessel’s interior in a rented warehouse in Brooklyn. She was making sure that the seven staterooms, along with the rest of the palatial accommodation, were just as she wanted them before Krupp’s men went to work.

Launched in April 1931, Hussar would take the Huttons around the Mediterranean, across the Atlantic and on to the Pacific and would spend up to nine months a year at sea until the couple divorced in August 1935.

The day after they parted for good, Edward signed the yacht over to Marjorie and shortly afterwards, on 15 December 1935, she married Joseph E Davies. The yacht was rechristened Sea Cloud in a break with the past, and when Davies assumed the office of American Ambassador in Moscow, Sea Cloud was stationed in Leningrad where she remained until June 1938.

Four years later, minus masts and bowsprit and painted grey, Sea Cloud was serving the United States Coast Guard as a weather station, patrolling between Greenland and the Azores and relaying data to Arlington, Virginia, every four hours.

The end of an era

At the end of the war, most large yacht owners realised that the game was up, some having already sold their vessels to the US Navy or the Coast Guard, but Marjorie set about restoring Sea Cloud and continued to use the big barque until the early 1950s when her marriage to Joe Davies hit the rocks.

Approaching 80 years of age and now starkly aware of the soaring cost of running the yacht, she sold Sea Cloud in 1955 to Generalissimo Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina, Dictator of the Dominican Republic, the self-styled El Jefe, known simply by his devoted subjects as The Goat.

Unfortunately for him, the Generalissimo did not have many years left in which to enjoy the vessel, which he re-named Angelita after his daughter, for he was shot and killed in Santo Domingo on 30 May 1961 by a group of men allegedly armed by the CIA.

His family fled the island with his body and large quantities of cash on board the barque but were intercepted at sea and forced to return.

Angelita was re-christened Patria and subsequently sold, refitted in Naples, re-named again (Antarna) and eventually seized in Panama. It was there that she lay in the torrid heat of Colon harbour for eight harsh years until 1978, when a group of businessmen led by Captain Hartmut Paschburg, brought her home to Hamburg and thence to Kiel for restoration at Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft (formerly Krupp Germania Werft). Exactly where she had been born 47 years before.

She emerged, eight months later, as Sea Cloud once again.

Phoenix rising

Another lady who got her yacht back from the navy was Mrs Horace Dodge, owner of Delphine, the dreadnought-bowed 78.60-metre Henry J Gielow-designed steamer, which had cost $US2.3 million to build in 1921.

The vessel was launched from the Great Lakes Engineering Works of Ecorse, Michigan. that summer and immediately set off for the Pacific via New England and the Caribbean with a crew of 55.

Sadly, Horace E Dodge (the automobile magnate) didn’t live to see his yacht completed, for he died in December 1920.

Mrs Dodge was with her second husband, Hugh Dillman, at the opera in New York when the vessel caught fire and sank in the Hudson River. Delphine was raised after 67 days and refurbished at a cost of almost $US1 million.

After the war, during which she was named USS Dauntless and served as the flagship of Admiral Ernest J King, Mrs Dodge Dillman spent another $US1 million restoring her and she continued to accommodate the family until 1962.

The almost obligatory period of neglect ensued but, like Sea Cloud and Savarona before her, she sails to this day. With any luck, this glamorous trio will soon be joined by a rejuvenated Nahlin, another great beauty from those halcyon yachting years.

An uncommon woman

While all this seems splendid in retrospect, not many women actually got to sail their yachts themselves during the first half of the 20th century.

There are photographs and paintings of ladies in hats and pretty dresses at the helm of yachts at Cowes and Newport, normally under the watchful eye of a sailing master. Rarer still are the images of women helming big boats, as Sis Hovey did onboard the J Class cutter Yankee during 1934.

Being a lady owner and skipper in that era was not the done thing – unless you were French, that is, and your name was Virginie Heriot.

Madame de la Mer, as her countrymen called her, was born in an enormous house named Villa Heriot at Le Vesinet, just outside Paris, during the summer of 1890. Her father, who owned the Grands Magasins du Louvre, died when she was nine, so it was her mother Anne Marie who nurtured her love of the sea.

A love that began with a long Mediterranean cruise aboard the family’s 59.75-metre steam yacht Katoomba, which had been built by Ailsa in Greenock for the Clark brothers of Paisley during 1898.

By the time she was 19, Virginie had logged 40,000 miles at sea and fortunately, the man she married the following year (Vicomte Francois Marie Haincque de Saint Senoch), was keen for her to continue.

In 1912, she commissioned Aile I, her first racing yacht. The couple was able to continue cruising in comfort with their son Hubert, however, for Katoomba (now re-christened Salvador) had been given to them by her mother as a wedding present.

The First World War obviously put paid to recreational seafaring and Virginie nearly died as a result of an operation in 1918 and it would appear that she felt from that point that her life would not be a long one.

She separated from her husband in 1921 and went to sea onboard the 1,492-tonne steam yacht Finlandia that she owned at the time. This would soon be replaced by the three-masted staysail schooner Ailee, itself a mother ship to her Eight and Six Metre Class racing yachts Aile and Petite Aile.

Her greatest achievement was winning a gold medal at the Amsterdam Olympics in 1928 onboard Aile VI and she would also triumph in the Coppa d’Italia over sailors from Argentina, England, Holland, Italy, Norway, Sweden and the United States.

She was awarded the Legion d’Honneur the same year and the British press was moved to describe her as the greatest yachtswoman in the world.

Virginie would continue to campaign her yachts and win races over the next three years, but the haunting premonition of an early demise stayed with her.

Early in 1932, she was making a passage from Venice toward Greece when her schooner encountered a storm and Virginie was thrown to the deck, breaking ribs and sustaining internal injuries. She subsequently refused to curtail her racing program and, in spite of various warnings, she brought Aile VII to the starting line at the Regates d’Arcachon on 27 August.

Virginie passed out during the race and died the following day aged 42. Although she had wanted to be buried at sea, her mother decided otherwise and Virginie was consigned to the family mausoleum at La Boissiere.

It was only when Anne Marie herself succumbed in 1948 that Virginie’s remains were eventually taken on board the French torpedo boat Basque and somewhere, not far from Brest on 28 June, Madame de la Mer slipped beneath the grey Atlantic waves forever.

Post-war racing

It was during the following year that the Hon Emily Rachel Pitt-Rivers (nee Forster) bought Foxhound, a 19.2-metre Charles E Nicholson-designed cutter, one of three built at Camper & Nicholsons during the 1930s to IRC 12 Metre Class scantlings.

The other two were named Bloodhound and Stiarna and the former would be Foxhound’s great rival in post-war British ocean racing under the ownership of Sir Myles Wyatt before he sold her to HM Queen Elizabeth (herself the owner of a substantial steam yacht named Britannia) in 1962.

These were not large yachts by comparison with the beautiful behemoths of the first 35 years of the 20th century, but they were about as big as anything racing anywhere else at the time, given the shortage of crew and the punitive taxation that were among the many other things owners had to face after the Second World War.

Ray (as she was known) Pitt-Rivers was an actress whose stage name was Mary Hinton and she was the daughter of Lord Forster who was the seventh Governor-General of Australia (1920–1925).

Her acting career would span more than 30 years from 1935 and she had been a keen Eight Metre Class helmswoman for much of this time. She had married and borne two sons and divided her spare time between London and Lepe, on the south coast of England, where she latterly lived close to her sister Dorothy, Lady Wardington. Both their brothers had been killed during the First World War.

What Ray Pitt-Rivers and Myles Wyatt did for both inshore and offshore racing in Britain with Foxhound and Bloodhound in the wake of the Second World War was more or less the same as King George V and Richard Lee had done with Britannia and Terpsichore (later Lulworth) after the First.

They got out there again, encouraged others to do so, and were at once fierce rivals and great friends.

Ray Pitt-Rivers became the first female Flag Officer of the Royal Ocean Racing Club and Myles Wyatt Admiral of the same and co-donor of the eponymous Admiral’s Cup. Ray would sell Foxhound toward the end of the 1950s, but not before she had attracted the attention of the American press too (most notably Sports Illustrated) for her performance in the 1956 Newport–Bermuda Race.

Foxhound was bought by a Portuguese owner and Ray would live to see her cherished yacht return to Cowes for the 1973 Admiral’s Cup series; by then the biggest boat in a large fleet and still among the fastest in the heavy weather that prevailed that August, although she was 38 years old.

Eyes on the prize

Yachts were becoming bigger again and the Observer Singlehanded Trans-Atlantic Race of 1972 had seen an extraordinary entry in the shape of Jean-Yves Terlain’s 39-metre, three-masted schooner Vendredi Treize.

Things got even crazier in the 1976 race when Alain Colas entered the 75-metre, four-masted schooner Club Mediterranee. Converted for charter work after the event, she would be billed as the largest sailing yacht in the world until Athena was launched in 2004 from Royal Huisman in Holland, by which time Mouna Ayoub had owned Phocea (as Club Mediterranee had become known) for seven years.

Mouna had bought the boat from Bernard Tapie, the colourful former president of the Olympique de Marseille soccer club, not long after her separation from Nasser al-Rashid, owner of the 106-metre motor yacht Lady Moura, and she went on to invest 20 million refitting her at Lurssen Werft in Bremen.

Not only was a lady owner spending on a scale unseen since the heady days of the 1930s, but she was disposing of some of the world’s largest yellow diamonds in the world along the way. One such stone fetched 2.52 million alone.

The fact that this Lebanese grande dame also owned the largest haute couture collection anywhere (over 10,000 items thus far and she’s still buying) was scintillating stuff and stories about her jewellery and clothes eclipsed accounts of the boat’s progress, even in the yachting media.

This was great news and the most captivating copy since Edward and Mrs Simpson were seen together on board Nahlin during the Mediterranean summer of 1936.

In fact, there’s still nothing quite like the suggestion that a lady may be in the market for a big boat to excite bankers and brokers, sailors and scribes alike.

Tip of the iceberg

The reported £60 million purchase of Tom Perkins’ 88.1-metre, state-of-the-art square-rigger Maltese Falcon by a hedge-fund manager named Elena Ambrosiadou generated as much interest in the hallowed halls of the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal as it did among the yachting press.

Ms Ambrosiadou admits to falling in love with the yacht during an Atlantic crossing but also allows that she is unlikely to spend much time onboard due to pressure of work. That is perhaps bad news from her point of view, for how can you own such a splendid sailing ship and stay away from her, however reluctantly. But it is good news for charterers who will have more dates to choose from when writing a cheque for £750,000 for a couple of weeks on the water.

The influence of women upon yachting is like the proverbial iceberg; the tip is visible, but not much else.

There are inshore and offshore racers, superyacht captains and crew, designers and builders, agents and chandlers, sailmakers and engineers, magazine owners and editors … the list goes on. There are those who invest their own time and talents incorporate and family-owned yachts of all sizes and bring their civilising touch to life at sea.

King Carol of Romania bought Nahlin from Lady Yule the year after she was chartered by Edward VIII and it is fair to say that both monarchs were unduly influenced by the women in their lives. In King Carol’s case, this was a spirited redhead named Magda Lupescu.

An excerpt from Time magazine in August 1937 reads as follows: “In Romania, where the Royal Family has never been rated wealthy enough to keep a $US1.35 million yacht, much less buy one, His Majesty’s purchase of the Nahlin came last week as a crashing fact to back up years of the rumour that Mme Lupescu is the shrewdest money-maker in Romania. She is said to have got her working capital from people who wanted things wheedled out of Carol II …”

Worse was to come

The excerpt continued, “Last week this able junk dealer’s daughter seemed on the point of realising a majestic ambition: a second Nahlin cruise, this time with the world’s tabloids headlining Mme Lupescu.”

Ouch! So she paid for the yacht, one assumes. Men didn’t like that in 1937, but it would be nice to think we are over it now.

As it happened, both kings enjoyed their sea time and King Carol was moved to say: “Nahlin is a beautiful vessel, one of the most splendid afloat. I need relief sometimes from state duties, and can think of few more pleasant ways of recuperating one’s energies, or refreshing one’s brain.”

And Edward VIII gave us one of yachting’s great quotations after his cruise onboard Henrietta Yule’s Nahlin: “The special charm of a large yacht lies in the circumstance that it enables presumably responsible people to combine, in a manner not otherwise possible, the milder irresponsibilities of a beachcomber’s existence with all the comforts of a luxury hotel.”

Even Enobarbus couldn’t have put it better than that!