Ocean keepers

Just as a number of marine conservation projects were building momentum, COVID-19 threw a pandemic-size spanner into the global works. But, as Charlotte Thomas discovers, the past year hasn’t been as big a write-off as you might imagine.

02 December 2021

For Clare Brook, CEO of the Blue Marine Foundation, one of the biggest challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic has been caretaking a forest of office plants that migrated home with her just before London’s first lockdown began in March 2020.

It seems somewhat incongruous to think that much could be done in marine conservation, promotion of the oceans’ health, or the advancement of a more sustainable boating industry under such stringent global restrictions, yet I am surprised to learn that rather than slow progress, Blue – and other NGOs and charitable foundations in the sector – have experienced something of a bloom.

“The weird thing about it all,” says Brook, “is not that we have had a whole cohort of new joiners at Blue over the past 12 months, but that none of us has ever met them.” For many of us, adapting to digital home working has been something of a natural progression.

But how do you monitor poaching or overfishing, or protect reefs, or educate indigenous populations when travel is strictly limited?

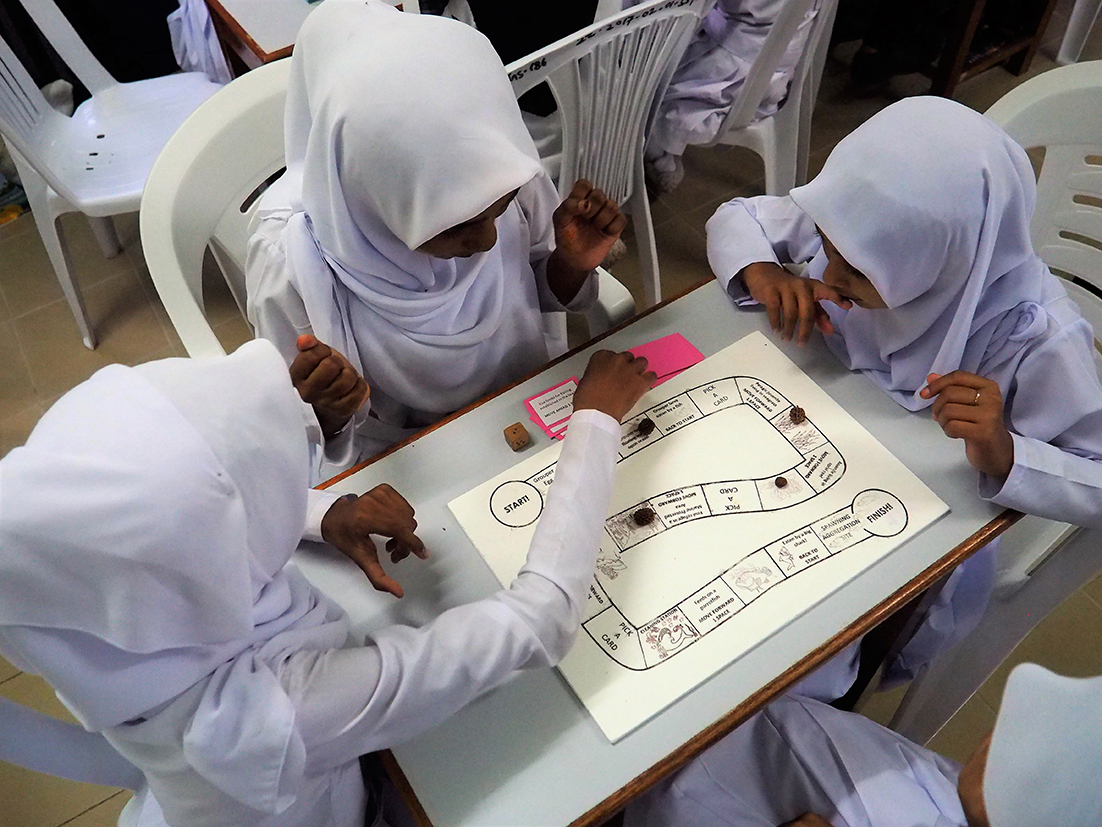

“We’ve learned that a lot can be done via the internet, even training – although it’s not as efficient in some cases, of course,” says Dr Andy Lewis of the Coral Sea Foundation, whose Sea Women of Melanesia project (SWoM) involves practical training, from dive instruction to underwater photography to how to use a GPS.

“Having said that, we’re aware of areas we’re involved where we do need to get back in there in person, but I don’t think that’s that far away with the vaccine rollout here in Australia.”

For Blue, there has been a coincidental focus on a diverse range of new elements, including development of online education resources, studies into ocean economics, the potential for oceans to mitigate climate change, and other facets that seek both to engage and elucidate an ever-expanding audience to the importance of our oceans, and in particular the damage that overfishing does.

But while this work can continue in the digital realm, with a stated aim to have 30 percent of the world’s oceans protected by 2030 and with projects underway all over the world, you have to wonder if the pandemic is affecting Blue’s work not only from an operational point of view, but also from a governmental or lobbying perspective.

“There is an element of COVID being a great excuse,” offers Brook. “Although, obviously, governments do have a huge amount on their plates at the moment. But – as ever – the ocean gets pushed right down to the bottom of the pile, or the argument is defined by fishing rights (as has been the case with Brexit in Europe), with no-one taking into account the actual health of the ocean – and the fact that maybe there are more purposes for the oceans than just plundering them for food.

“Blue is focusing very intently on the area of blue carbon: the extent to which the ocean has nature-based solutions for climate change,” she continues.

“Some very interesting papers came out in the past year that have furthered the knowledge on just how much carbon these various habitats store – it’s still early days in terms of the science, but that’s been a big leap forward.”

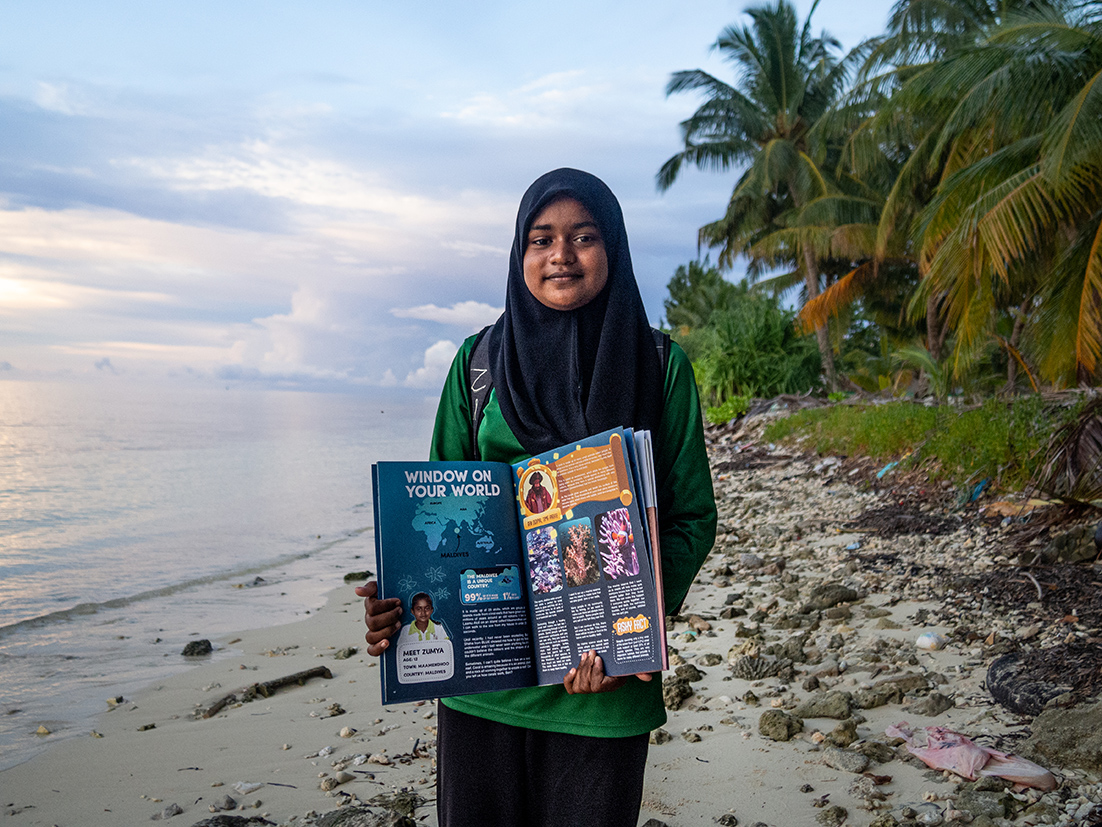

While overfishing has been the linchpin of Blue’s campaign, fishing has also been a key thrust of SWoM, one of the ultimate aims of which is to demonstrate that careful curation of fishing grounds and reefs means a more sustainable food source – essentially empowering local people to be the advocates for marine conservation.

For Lewis, adapting to the new normal has been made easier thanks to the fortuitous timing of the first stages of the Sea Women project.

Since the project began in 2017, by the start of the pandemic some 30 women from Papua New Guinea (PNG), the Solomons and other areas within the Coral Triangle had been trained by Lewis and his team in marine conservation and surveying, diving and other aspects crucial to them being able to monitor their environments and even undertake research work.

“The investment we made in that training paid huge dividends in the past year,” Dr Lewis enthuses.

“We pretty much met the major goals we had set in terms of women trained, marine reserves proposed, underwater imagery collected. Supporting and training local people was always a part of our strategy and philosophy anyway, because you can’t come into these cultures as an outsider and start telling people where they can and can’t fish.

“Ideally, we would have got out there again to train the women further, but instead we just threw them in the deep end to start their coral reef science and marine conservation expeditions in Melanesia – and because of their backgrounds and experience up there, none of it is particularly challenging for them!”

For Lewis, it has meant implementing a weekly routine to ensure the projects were advancing as close as possible to the pre-pandemic plan.

“Every Monday I would check in with my teams in the Solomon Islands and PNG, and then we would just set a work plan for the week; they would keep track of their funding and expenses and I’d send them top-ups when necessary to ensure they could keep doing the work.

There was enough internet connection into the Solomons and PNG that even if they took a day to upload, the images from a whole survey would still upload, ready for us to download them at our end. And because everything was taken with geo-tagging cameras, we could see exactly where an image was taken and at what time of day.

He continues, “The most important thing is that we also managed to keep the program expanding – we realised there was a large pool of women attending university in Port Moresby who were already educated and passionate about conservation, and many of them were from the marine provinces of PNG.

“We tapped into that resource with online learning and, with our local teams running weekly meetings for the women who were studying, we were still able to get them dive training in PNG.”

Another facet that the Sea Women highlighted was the opportunity afforded through social media, particularly in reaching younger (and often more environmentally aware) audiences. Indeed, says Lewis, many of the Sea Women boast thousands of followers.

Lewis has also been opening local offices to assist with other elements too, including the logistics of arranging trips, paying for boats, meeting with land-owners, printing materials and distributing aid and even T-shirts. “It’s one thing to train someone to dive and take underwater photos, but they have to have the gear, the team and the resources to do all the other stuff.”

The pandemic may have had a negative affect on some aspects of wildlife and marine conservation, but restrictions on travel and in other areas can have a direct (positive) impact on the wildlife or the environments themselves too, as WildAid CEO Peter Knights points out.

“While some field operations have slowed down, and while we haven’t been able to meet people in person, some of the industries that we are up against, such as the bushmeat trade, have also slowed down. Poaching, for example, has gone down because people can’t travel and the markets haven’t been open.

“However, in the longer term, we worry that a lack of tourism – for example, going on safari in Africa – can impact local people’s incomes and therefore they will get more desperate. In places like the Galápagos, there used to be lots of tourist boats that would be on the lookout for illegal fishing activity. You don’t have that at the moment so it’s a bit of a mixed bag in the field.”

As Knights and others point out, though, one thing that’s clear is that people have become more acutely aware of the environment and conservation over the past year, either because they’ve had more time to think about things, because they’ve seen how pollution has dropped, or because there is a clearer understanding that COVID-19 is linked to wildlife and bushmeat practices. “Experts are pretty certain that COVID-19 originated in horseshoe bats, but there’s usually a vector species in between,” Knights explains.

Viruses and diseases can be brought on in those species – hunted in the forests but brought into city centre markets alive – through stress. “You couldn’t design a better transmission mechanism,” Knights continues. “We hope governments take warning from COVID-19.”

Increased awareness, however, doesn’t always translate into the other element of any NGO’s operation – funding. Whether it comes through charitable giving or grants, it’s an area that could have been severely dented over the past year, but the consensus seems to be that the impact is not as large as might have been feared, not least because the financial markets in general have remained stable.

“It’s not a good time to bring in new donors right now,” offers Knights. “But I have to be very grateful for the way existing donors have stuck with us. Some have even increased their gifts.” For Lewis, there are still a few unknowns regarding the state of the grants process, but also some encouraging signs.

“We’ve certainly got a lot of grant applications in and under consideration,” he says. “We also have several grant-making agencies starting to contact us because we’re getting results in a part of the world where it is difficult to get results.

“We’re also extremely fortunate to have a number of philanthropic backers who have been behind us from the start, and they’ve not waned in their support at all. We used to have events for donors. Now we have fireside chats, which are literally me sitting next to my fire on Zoom,” Knights says.

“It’s a lot more convenient to not have to go anywhere, and as we can do a lot of small ones, it actually becomes far more intimate. I think we will retain that going forward, although I think what is harder to avoid is the first meeting – you need that to build trust, particularly with, for example, a government minister or a celebrity.

“But we will do a lot more by internet and part of what’s happened over the past year is that a lot of places where the internet wasn’t working very well have really upped their game. That means the world is more interconnected and that’s a very positive thing.”

The move toward more digital and remote working has broader implications. In the Galápagos, for example, WildAid is promoting a stationary vessel monitoring system.

“It basically surveys the entire marine reserve from an office on a computer via satellite,” Knights says. “That’s the kind of technology that can really deliver effectiveness – it’s essentially 100 percent coverage but doesn’t involve a lot of humanpower, and it’s way cheaper. That’s what we’re trying to promote as affordable enforcement, and we’re able to do a lot of that virtually.”

For some, the focus on marine conservation is more indirect. The Water Revolution Foundation (WRF), for example, is a relatively new body established at the end of 2018 with the aim of driving sustainability in the superyacht industry and preserving the world’s oceans through the neutralising of the industry’s ecological footprint.

The timing hasn’t been ideal but, momentum is building. “The attention to sustainability in the yachting industry is really growing, which is a good thing, and that has resulted in a lot of interest and new partnerships,” says WRF Executive Director Robert van Tol.

“It could easily have gone the other way because I recognise that people have had different priorities, especially shipyards. As we are just starting out, you have to get reach, and that’s harder with a lack of industry events and networking opportunities.”

For many, video conferencing – combined with people generally travelling less and having more time – has been a bit of a boon. Moreover, some of the companies and suppliers who were emerging with sustainable solutions, and had previously struggled to get airtime, now have more of a platform – particularly as WRF is compiling a verified database of sustainable solutions.

Another key development that has been in the works and unaffected by the pandemic will be coming soon – the Yacht Environmental Transparency Index, of which a working calculation method was due to be shared with the industry in March 2021 for feedback, in spite of some earlier delays due to the pandemic. Watch this space. It’s clear that not everything can be done remotely.

There is, according to Lewis, evidence that the economic downturn as a result of the pandemic is impacting security in places like PNG, which can directly impact local teams working there as well as affecting the wider goals of the projects. However, it also presents new opportunities to win local hearts and minds in the not-so-distant future.

“There will be huge benefits in being the first vessels back in there,” says Lewis.

“Bringing aid and medical support and letting the people know that the world hasn’t forgotten them – not to mention telling them we’re still interested in helping them because their custodianship of their marine resources is valuable on a global scale.”

For most, however, some of the enforced changes of the past year will definitely stick. “We’ll never go back to working the same way again,” says Brook.

“I think everyone agrees that video meetings can get tiring, but the speed at which we can all work and the effectiveness of communications has been a major thing. Plus, we have a lot of people working for Blue who aren’t based in London and it’s been much nicer for them to be connected.” As for any lasting impact on targets, like Lewis, Knights and van Tol, Brook paints a positive picture of how longer-term goals and target dates have remained broadly unaffected.

“The innovative nature of Blue Investigations, Blue Education, Blue Economics, Blue Legal and Blue Carbon is thrilling. We’re still absolutely set on our 30 percent of oceans protected by 2030 goal, and Blue Carbon in particular is going to make all the difference,” she concludes. We can only hope the progress made against the odds in the past year can be maintained across the board, because our oceans need all the help they can get – pandemic or not.

bluemarinefoundation.com

coralseafoundation.net

waterrevolutionfoundation.org

wildaid.org