Moral compass

It’s been said that if you can’t save the Galapagos, you can’t save humanity. The mystical islands are buckling under the weight of tourist numbers, but there are those like Frederico Angermeyer who are making a difference.

Written by Scott Alle

07 June 2018

Islands are my favourite places. But recently, a news feed delivered images of Maya Bay on Koh Phi Phi Leh in Thailand – the once idyllic location for the dark backpacker film The Beach – choked with plastic bags and plastic detritus.

Swarming numbers of up to 5,000 tourists a day has resulted in severe damage to Koh Phi Phi’s fragile ecosystem. Thai authorities will close the azure cove for four months, but experts warn only a total visitor ban can make a difference.

It’s too late for Maya Bay. And depending on who you talk to, the Galapagos Islands – the epitome of biological diversity – is heading the same way.

A rising tide of “eco-tourists”– 225,000 a year in some places – appears to be overwhelming this amazing island chain 600 nautical miles (1100 kilometres), into the Pacific off the coast of Ecuador.

Travel writers have panned the harbour of Puerto Ayora in the main town on the island of Santa Cruz as polluted and overcrowded. As far back as 2012, Carole Cadwalladr in The Guardian reported “a filmy slick of oil shines on the surface of the water where hundreds of boats wait to receive the next intake of tourists.”

She also highlighted the lack of controlled development, criticising “a mess of shanty suburbs and half-finished hotels. The ground water is contaminated and there’s no proper sewerage.”

Six years on, the pressure created by the deluge of tourists only seems to have worsened. In February, The International Galapagos Tour Operators Association (IGTOA) wrote to Ecuador’s tourism minister, expressing concern that the rate of growth in land-based tourism over the last decade is unsustainable. Worse, it may result in irreversible harm to the islands’ famed ecosystems and extraordinary wildlife.

The international media is beginning to take note of the potential implications of this uncontrolled tourism growth too. Both CNN and guidebook publisher Fodor’s recently placed the islands on their list of destinations not to visit in 2018, citing concerns about the increasingly negative impact of tourism.

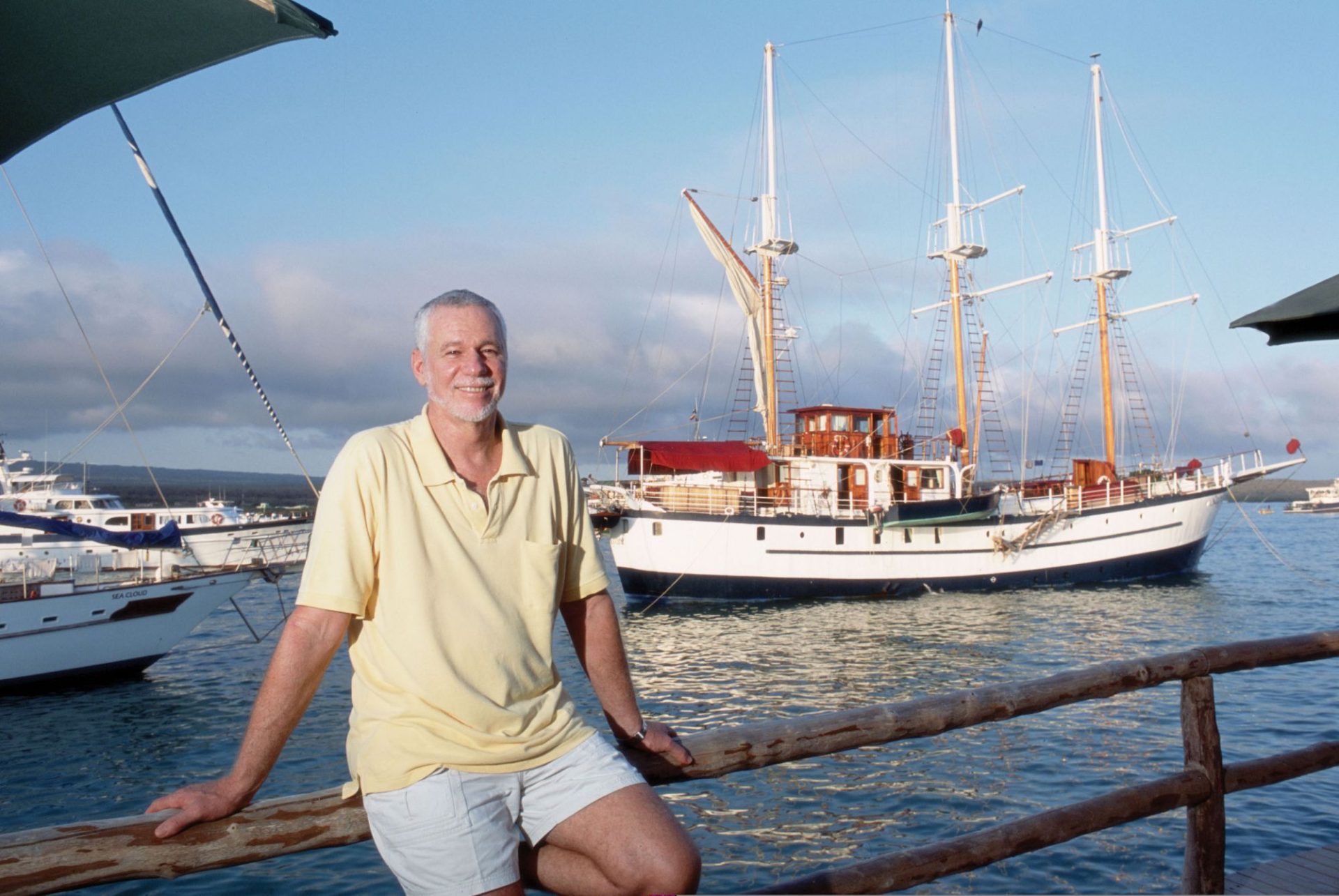

But one of the island’s best-known sons, passionate conservation advocate Federico (or “Fiddi”) Angermeyer isn’t convinced that numbers should be curtailed.

“Galapagos wouldn’t exist without tourism,” he flatly states.

Firstly, he argues, “It wouldn’t be a national park,” which it was declared in 1959, covering 97 percent of the islands plus a marine reserve spanning 138,000 square kilometres. “We need the tourism,” he continues.

“It might be a dream to take the islands and leave them completely natural, perhaps just for scientific use, but there would not be enough funding for it. Fishing would take over, the Japanese fishing boats would come in,” he warns.

“The islands would definitely be destroyed in my opinion.”

On the face of it, you would expect Angermeyer to say that. He runs two of the archipelagos’ biggest cruise vessels: the Mary Anne, an elegant 66-metre (216-foot) barquentine; and Passion, a beautiful 48.5-metre (160-foot), totally refurbished superyacht capable of accommodating 12 passengers in four luxurious cabins and two suites.

Yet if you dig deeper into Angermeyer’s story – and read up on the successful conservation programs that have brought several iconic Galapagos species back from brink (giant tortoises and marine iguanas), or are in the process of being saved (mangrove finch), as well as other initiatives to deal with invasive species (rats and ants) – then you start to get a more complete picture of the situation.

Young Angermeyer and his family were among the first to permanently live among the stunning array of wildlife of the Galapagos. The giant land tortoises, sea-lions, sea turtles, whale sharks and whales, as well as the crested black iguanas – the world’s only sea-dwelling lizards. Darwin described them as “imps of darkness”, and used them to help formulate his seminal Origin of the species.

Angermeyer’s father Fritz, and his brothers, escaped Germany in 1937. They were planning on sailing what would have been a truly epic voyage on their own stout Baltic trader, but a lack of funds meant they had to sell the boat and book a passage on a ship.

His mother Carmen arrived in the islands as a six-year-old from Spain in 1934. Now 90, she is one of the last remaining pioneers. She home-schooled her son in three languages; German, English and Spanish. “It would have been better if it was in the reverse order,” Angermeyer jokes.

Family snaps show a huge lobster being held up by a strong-looking, blonde-haired boy of about six or seven – the giant crustacean is half as long as him. Thanks to a 20-year campaign combining regulation and education of the islands’ fisherman, there are still good catches of the local red and green lobster varieties.

For Angermeyer, hours and hours out in small boats exploring the islands’ rugged, unforgiving lava shorelines forged a self-reliance and deep connection with nature. “In retrospect, it was very special. At the time, maybe a little lonely,” he qualifies.

His father taught him “to respect the ocean, and the strength of it. If you are going to go out there, you need to be prepared.”

It’s a lesson he has never forgotten: “I was taught when you went on a boat you had water and all the possible survival tools you might need at hand.”

His apprenticeship in the ways of the sea was backed up by solid experience in his twenties aboard a diverse range of vessels, including a stint on a boat associated with the world-renowned Charles Darwin Research Center, which conducts research and environmental education for conservation.

A variety of roles included skipper, deckhand, cook, and the worst job on any boat – toilet fixer. Running his own tours, Angermeyer quickly realised the further away his guests were from the comforts of civilisation, the more they appreciated them.

“I was one of the first owners to have a boat that had private baths for each cabin. That was a big deal,” he recalls.

“When we first started, everyone just slept on a deck together. I went by what I liked and wanted. I was one of the first to install air conditioning because I wanted it in my cabin; I was looking for more comfort myself.”

Sustainability was an early priority too, and Angermeyer played a key role in instigating the current format of two-week itineraries to ease the pressure on sites. Some companies are now pushing for that to be further restricted to just one week.

“Generally speaking, we’ve got 97 percent of the islands as national park, with three percent developed,” he explains.

“There are very strict rules. Every group of tourists has a guide, who indirectly controls and patrols; the tourists have to stick to the paths on land.”

But those environmental safeguards may need to be further tightened. From the 1970s to the early 2000s, the vast majority of Galapagos tourists participated in ship-based tourism, which has been hailed as a model for limited, well-regulated tourism.

Strict quotas exist on the total number of berths allowed on the Galapagos cruise ship fleet, and there is a cap of 100 as the maximum number of passengers any ship can carry. There are no similar restrictions or regulations governing land-based tourism, and if the current rate of growth continues unabated, in less than 35 years there will be more than one million visitors per year to the Galapagos Islands.

But for Angermeyer, there’s an even more potent – and immediate – threat to the life-giving aquamarine waters that crash onto the Galapagos’ shores: plastic bags. Banned in the islands, you don’t have to venture far from the archipelago before encountering the scourge of plastic pollution.

Interviewed for Sail America, the peak industry body for US sailing, he described a disturbing scene off the Galapagos where rubbish caught in two currents floated for miles, and a freezer drifted by. There are other, far worse silent killing grounds pockmarking the ocean too, and they are growing in size.

Angermeyer is adamant it is challenge that has to be tackled. “The real area where you see plastics like crazy is the Gulf of Panama,” he relates.

“The currents go in a circle and the plastic just stays there. Many people are trying to find a solution, but I think we need to do the same thing as WildAid, which is to stop buying plastic.

“Instead of asking people to recycle, we should start talking to manufacturers regarding packaging, and ask them to use less plastic,” he urges.

He cites the wrapping of individual pieces of fruit and plastic drink straws and garnishes, as completely unnecessary and likely to end up in some sea animal’s stomach.

Angermeyer is backing his words with concrete actions. He donates one charter every year aboard Passion (re-named WildAid Passion), to WildAid Galapagos. [See wildaid.org/protecting-the-galapagos-with-angermeyer-cruises for more information]. At the last auction for the spot, the successful bidder forked out $200,000 US dollars for the one-week trip, which went directly to the national park.

In addition, a hundred dollars of the revenue generated by each passenger fare goes to the Galapagos Conservation Fund to support the battle against introduced species and the fight to stop illegal fishing.

But Angermeyer envisages a greater alliance that could lobby plastics manufacturers with a united voice:

“Ocean conservation groups such as Blue Marine, Mission Blue, and WildAid need to start talking with one another and working together,” he says.“I don’t know yet [how to achieve that]. I’m definitely trying to make contact with everyone because it has to be done.”

According to Angermeyer, giving conservation a commercial value is perhaps the best way of facilitating much-desired change. “If we could make ocean conservation a money-maker, a profitable business, you’re going to get a lot of people involved,” he enthuses.

Yet still more opportunities exist to protect and improve the crucial ocean environments of the Galapagos and beyond, and we need more champions like Angermeyer to galvanise the rest of us into creating this imperative change.