Lest We Forget

In the second part of our feature on the Silentworld Foundation, we take a closer look at two of its most significant recent discoveries – the submarine HMAS AE1, which disappeared during World War I, and the Montevideo Maru, which sank without a trace off the Philippines in World War II, claiming the lives of more Australians in one disaster than the entire Vietnam War.

Photography by Silentworld Foundation Photography and Australian Navy

11 January 2024

Solving these mysteries is not just piecing together our maritime history, however – it’s finally laying those lost to rest, and bringing a sense of peace to their descendants.

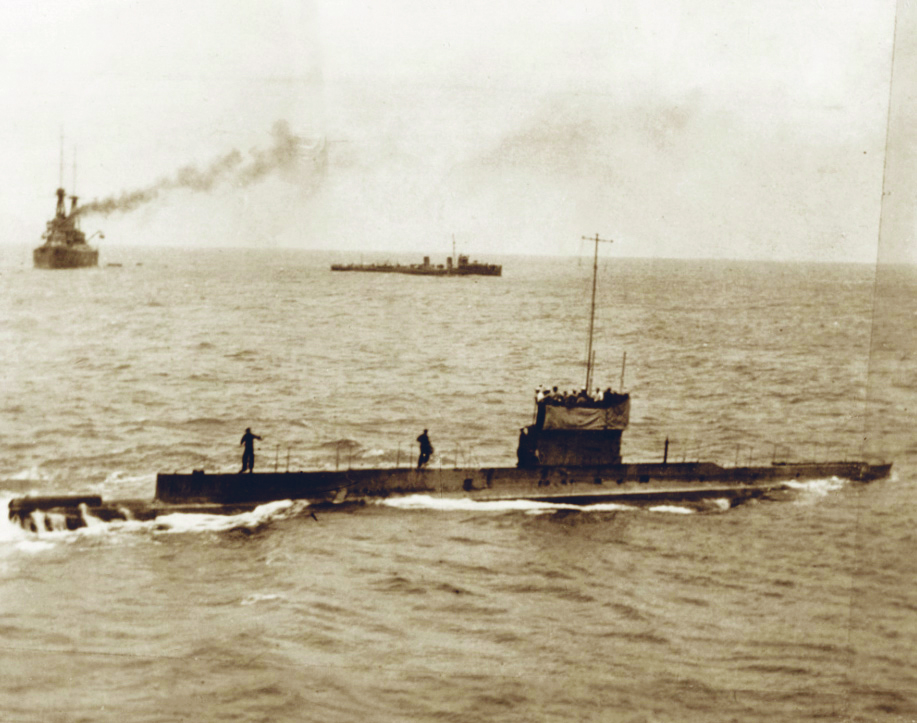

Although relatively recent, Australia’s wartime past has been instrumental in the development of the nation’s identity. Indeed, when World War I broke out, the Royal Australian Navy was only three years old – but it possessed one of the most technologically advanced weapon systems in the world in the newly acquired submarines HMAS AE1 and HMAS AE2.

The first submarine to break through the Dardanelles Strait, AE2 is well known for the action it saw during the Gallipoli campaign. Its fate was well documented too, with the site of the wreckage found, recorded and subsequently protected. However, the circumstances surrounding the loss of AE1 was far more mysterious.

Assigned to support operations in German New Guinea, on 14 September 1914 AE1 was patrolling off Cape Gazelle. After making contact with HMAS Parramatta, AE1 continued the patrol with instructions to return to port in Rabaul by sundown. HMAS AE1 never returned.

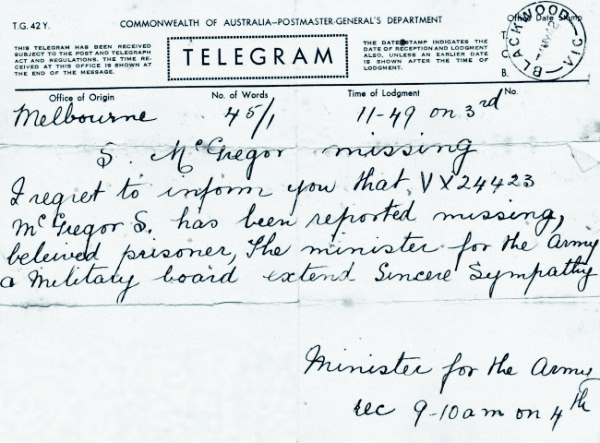

A search that continued for three days was mounted to locate the vessel, but no sign of it was ever found and the fate of the vessel and the 35 men on board, comprising Australian, New Zealand and British subjects, remained a mystery for over a century.

That was until the Silentworld Foundation and the Australian Government, through the Royal Australian Navy, co-funded an expedition to search for AE1 again, in collaboration with the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM), the Submarine Institute of Australia and Find AE1 Ltd, a company established with the sole purpose of locating the vessel, which comprised the team that located AE2.

The team partnered with Fugro, an international commercial surveying services company, and over a hundred years after the submarine’s disappearance, they set out aboard M/V Fugro Equator to find those lost on board AE1. On the evening of 20 December 2017, data from the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) revealed that sonars had detected a wreck with dimensions similar to the lost submarine. AE1 had been found.

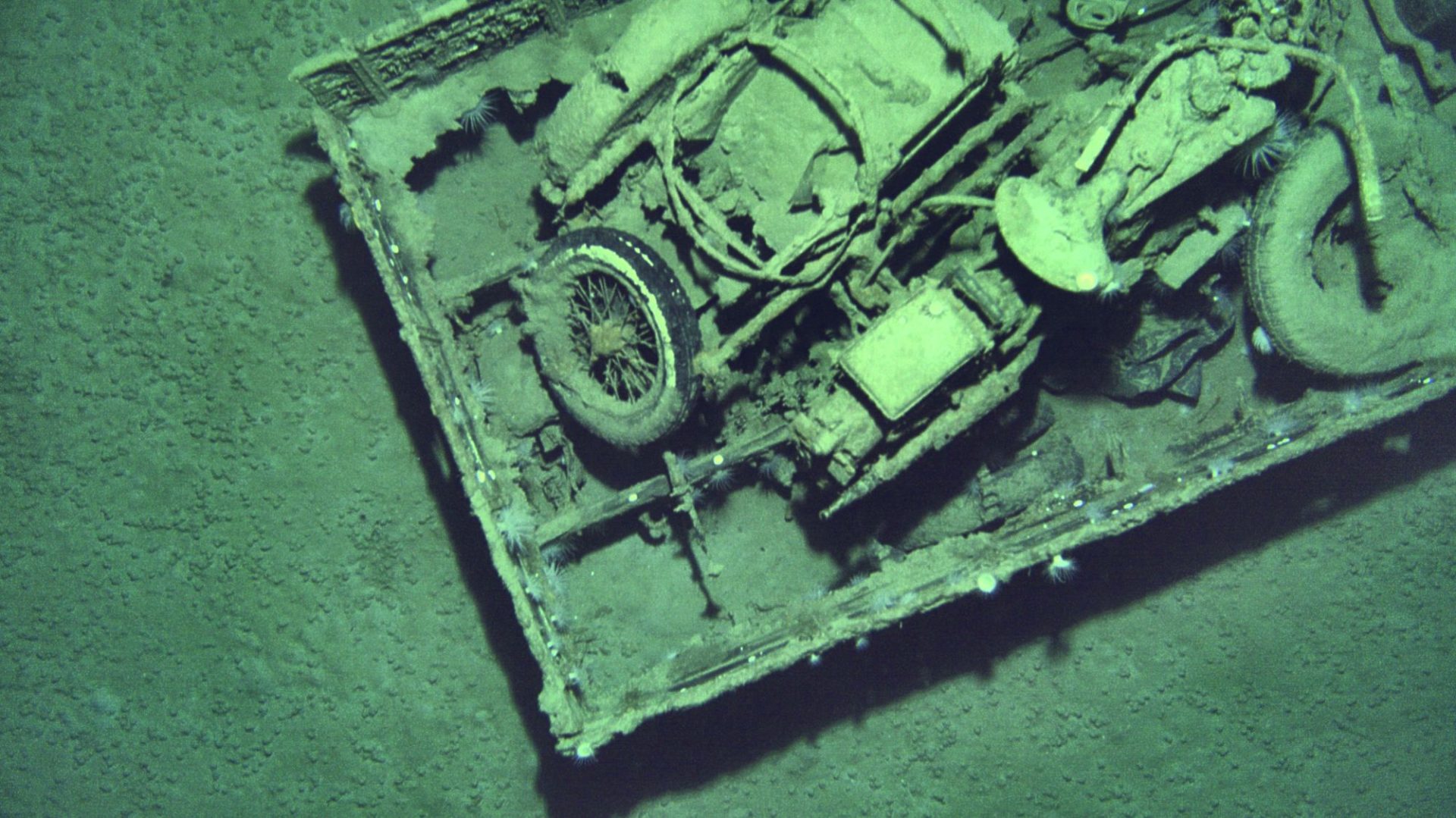

Not long after, in 2018, an expedition to record the submarine in detail was undertaken by Find AE1 Ltd and the ANMM, along with Curtin University, aboard the Vulcan Inc vessel Petrel. Most pertinently, still and video footage from the expedition analysed by the team led to the discovery of the most probable cause of the disaster – a partially open critical ventilation valve in the hull.

The Australian National Maritime Museum states, “The valve should have been closed before diving. When the submarine dived, the partially open valve would have allowed water to flood the engine room, which may have resulted in a loss of control, causing the submarine to descend below its crush depth of 100 metres. The resultant implosion would have killed the crew instantly.”

While the reason the valve is partially open remains unknown, the discovery has allowed the descendants significant closure, spurring the Silentworld Foundation on to continue such important work.

Mysteries no more

As Director and Founder of the Silentworld Foundation John Mullen explains, “After our success with the submarine AE1, we brainstormed what other significant shipwrecks were important to Australia and represented a mystery or major technical challenge to locate.

“We then spent a long time liaising with researchers, historians and others before deciding to take on the SS Montevideo Maru project, a Japanese merchant vessel that was not marked as a POW carrier and subsequently torpedoed and sunk by the submarine USS Sturgeon.”

With more than twice the number of Australians lost on the Montevideo Maru as those during the Vietnam War, it quickly became apparent that this was a tale that had not been fully told – and one that still had a significant impact on the families of those lost, both then and now.

“The project has been a long time coming, with researchers from the USA, Japan and Australia dedicating all the resources available to create the best formula for success,” says Mullen, who was responsible for the initiative. “With the cost of mounting a project such as this, we knew we only had one shot, so wanted to ensure we had all the information available.”

And so, the planning to find the Montevideo Maru began. But, like many projects, there were obstacles. First, determining the wreck’s location was challenging as the information in the available records conflicted. Then there was the technical challenge of finding a shipwreck at such an extreme depth – even deeper than the Titanic. The expedition also needed extremely limited specialist equipment to operate at these depths and required significant funding.

Having established an agreed partnership with Fugro, the Silentworld Foundation approached Unrecovered War Casualties– Army (UWC-A) with a funding proposal. The role of the UWC-A is to investigate the fate of missing Australian service members, and the Silentworld Foundation’s proposal to locate the final resting place of the Australian service members on board the Montevideo Maru was aligned with their goals. The search was on.

Casualties of war

The story of the Montevideo Maru began in the mid-1920s, when the Osaka-based shipping line, the Osaka Shosen Kaisha (OSK), placed an order at the Mitsubishi Zozen Kakoki Kaisha dockyard for three ships to carry passengers and goods in support of Japan’s emigration program to South America.

The Montevideo Maru, launched in 1926, was among them. However, when Japan entered the World War II in 1941, these ships and many others were requisitioned by the government for use by the Imperial Japanese Navy. That was until the following year – 1942 – when Rabaul, the administrative capital of the Australian Mandated Territory of New Guinea, fell to Japanese forces on 23 January.

Australian forces stationed in Rabaul were captured and imprisoned along with civilians, and ships such as the Montevideo Maru were then used to transport prisoners of war, together with cargo and Japanese troops. As such, they weren’t eligible to be marked as non-combatants – and consequently, many met their end under fire by Allied forces, which had no way of knowing they carried Allied prisoners.

The Montevideo Maru had arrived at the port of Rabaul on 9 June 1942. Thirteen days later, 1,053 prisoners were transferred to the ship for transportation to Hainan Island, a Japanese air base off the coast of mainland China, where labour was needed to develop agriculture and industry.

On the night of 30 June, the Montevideo Maru passed through the Babuyan Channel to the north of Luzon, an island in the Philippines, where it was sighted by the USS Sturgeon, an American Salmon-class submarine armed with eight 21-inch torpedo tubes. The ship was proceeding at its best speed on a course for Hainan Island and, according to the submarine’s logs and subsequent report, the Sturgeon, on its fourth patrol at the time, gave chase.

According to reports by the Sturgeon, at 0225 on 1 July, one of the four torpedoes fired by the submarine struck the Montevideo Maru and exploded. The ship quickly assumed a severe list to starboard and began to sink rapidly by the stern. Within 11 minutes of the torpedo strike, the vessel slipped beneath the surface.

Until recently, there was no clear indication of the exact number of Australian nationals that perished during the sinking of the Montevideo Maru. However, a 2012 translation of the Japanese manifest revealed approximately 979 Australians were lost with the ship. Of this number, around 852 were military personnel, along with 201 civilians from 14 countries.

According to the Osaka Shosen Kaisha Owner’s Report on the loss of the Montevideo Maru, 102 Japanese nationals out of a total of 122 crew and guards survived the Montevideo Maru sinking, of which only 26 Japanese nationals were able to make their way to Manilla.

It is also believed that approximately 24 crewmen from the Norwegian defensively equipped merchant ship M/V Herstein were also imprisoned aboard the Montevideo Maru at the time of its sinking. The Norwegian freighter was in the service of Allied forces after Norway fell to Germany and, having transported troops to Rabaul by way of Port Moresby, was docked when Japanese bombers attacked the port as a prelude to their invasion.

Reason to hope

During the expedition, the Silentworld Foundation was conscious of the need for both confidentiality and to maintain a low profile – the search area is in the West Philippine Sea and under Philippine control, but it also falls within the Nine Dash Line claimed by China. To help prevent an event, the foundation liaised with the Australian, Philippine and Japanese governments well before the expedition on 1 April 2023.

As the Silentworld Foundation boarded the Fugro Equator in Port San Fernando on the West Coast of Luzon in the Philippines, one of the Japanese researchers presented the team with traditional Japanese Daruma dolls – symbols of perseverance and luck, they were given to bring focus to the search. Both the onboard and shoreside teams coloured in one eye of their respective dolls, and the search began in earnest.

As the Fugro Equator sailed toward the search area, calibrations were made of the AUV to ensure the equipment would be reliable in the required depths. Next, the Silentworld Foundation and Fugro Equator teams ran nine missions of between 36 and 48 hours each, with every mission also involving an extra 24 hours to download the data from the autonomous underwater vehicle.

With some redundant time between searches due to weather, on 18 April, after a three-week search, there were clear signs the expedition team had located what they believed to be the wreck of the Montevideo Maru in the Philippine Sea, some 129 kilometres off Cape Bojeador.

Lying at a depth of 4,175 metres, the ship had broken in two but was otherwise well preserved and retained sufficient features for the team to positively identify the wreck as the Montevideo Maru.

“Once the vessel was located, it was paramount to ensure that the vessel we had found was indeed the Montevideo Maru and not another that had also fallen to war,” says Captain Michael Gooding, Manager of the Silentworld Foundation. “With the aptly named war room adorned with the images of those who had lost their lives, the team set about comparing details of the ship found to Lloyd’s drawings and other accounts.

“The decision to put our hands on our hearts and declare we had found the Montevideo Maru was not taken lightly and took some thorough analysis and liaising with Unrecovered War Casualties–Army to ensure we were all comfortable with the decision,” notes Gooding. “It wasn’t until 22 April that we went public, and it was with great pleasure that the teams coloured in the second eye of the Daruma dolls to give thanks for the successful mission.”

The team had pre-planned for the eventuality of finding the ship and had brought fresh flower wreaths from the Philippines to respectfully perform a ceremony above the location where she lay. “With sombre tones and heartfelt emotion, the team performed a special memorial at sea,” remembers Gooding, who notes the rewards of such expeditions lie firmly with the relatives of those left behind.

“We received hundreds of messages from families who had never given up hope that one day they would find the final resting place of their loved ones,” says Gooding. “After 81 years of not knowing where their fathers, uncles and great-grandfathers lay to rest, the outpouring of messages from relatives was sincere and well worth the effort to find the vessel.”