Cause for hope

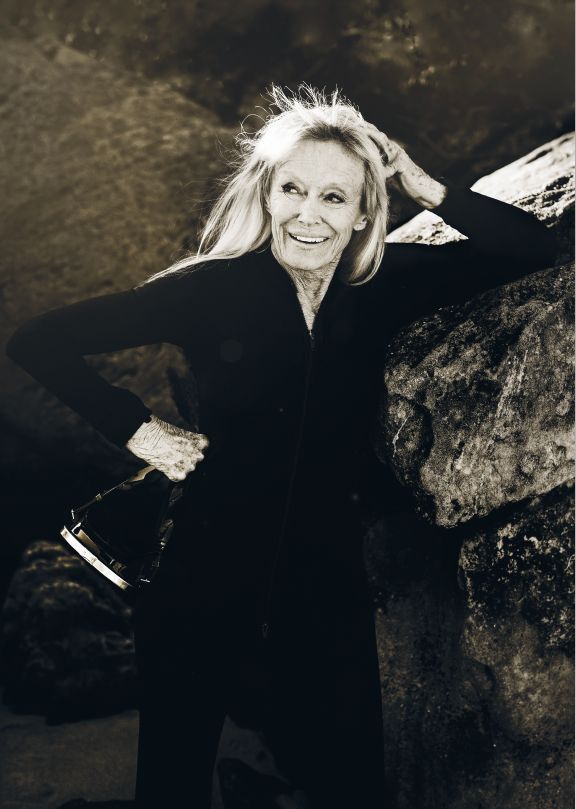

Diver and conservationist Valerie Taylor AM has dedicated six decades to sharing her fascination with the ocean and dispelling myths associated with sharks. Now, with counts of grey nurse sharks significantly lower than anticipated, the next phase of her advocacy has begun.

Written by Jeni Bone

Photography by Kara Rosenlund

01 February 2024

There can’t be many people on the planet who haven’t seen or at least heard of the 1975 triple Academy Award-winning film Jaws – the world’s first blockbuster and 26-year-old Steven Spielberg’s second movie.

A watershed moment in cinematography, raking in billions of dollars worldwide in ticket sales, merchandise and sequels, Jaws is a cultural phenomenon.

Some 50 years later, it’s also considered the trigger of human beings’ deep-seated fear of these majestic apex predators, which led to their slaughter in astonishing numbers.

Fewer people would know that Ron and Valerie Taylor, pioneers in marine documentary and the study of these cartilaginous fish – of which there are 500 species, dating back 350 million years – were creative collaborators in the film.

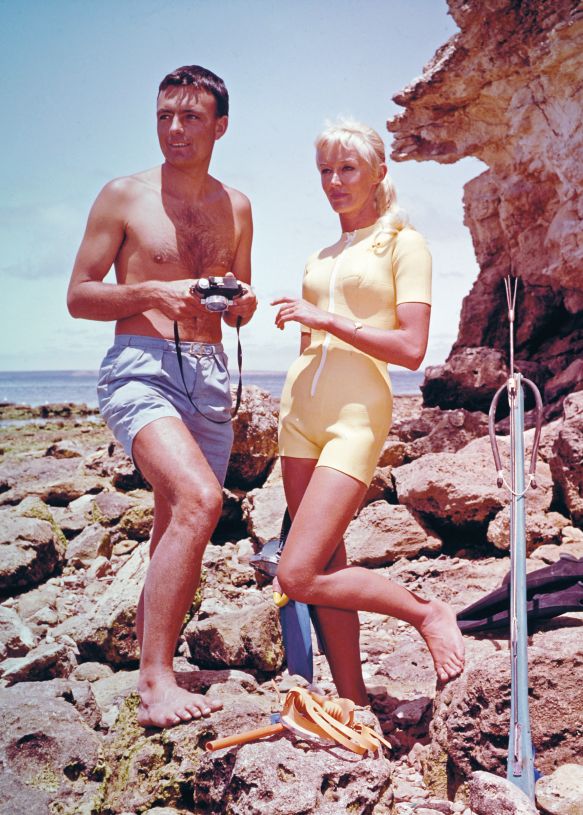

Australia’s golden couple, spearfishing champions and contemporaries of Jacques Cousteau, shot the live-action footage of a great white entangled in the metal cage at Dangerous Reef in South Australia.

Bruce, as the animatronic shark was known, may have been the scene-stealer, but the real shark sequence, filmed by Valerie and Ron, created a tidal wave of fear across the globe – and is but one chapter in the extraordinary life of Valerie Taylor, trailblazing conservationist and living legend, more at home beneath the waves than above.

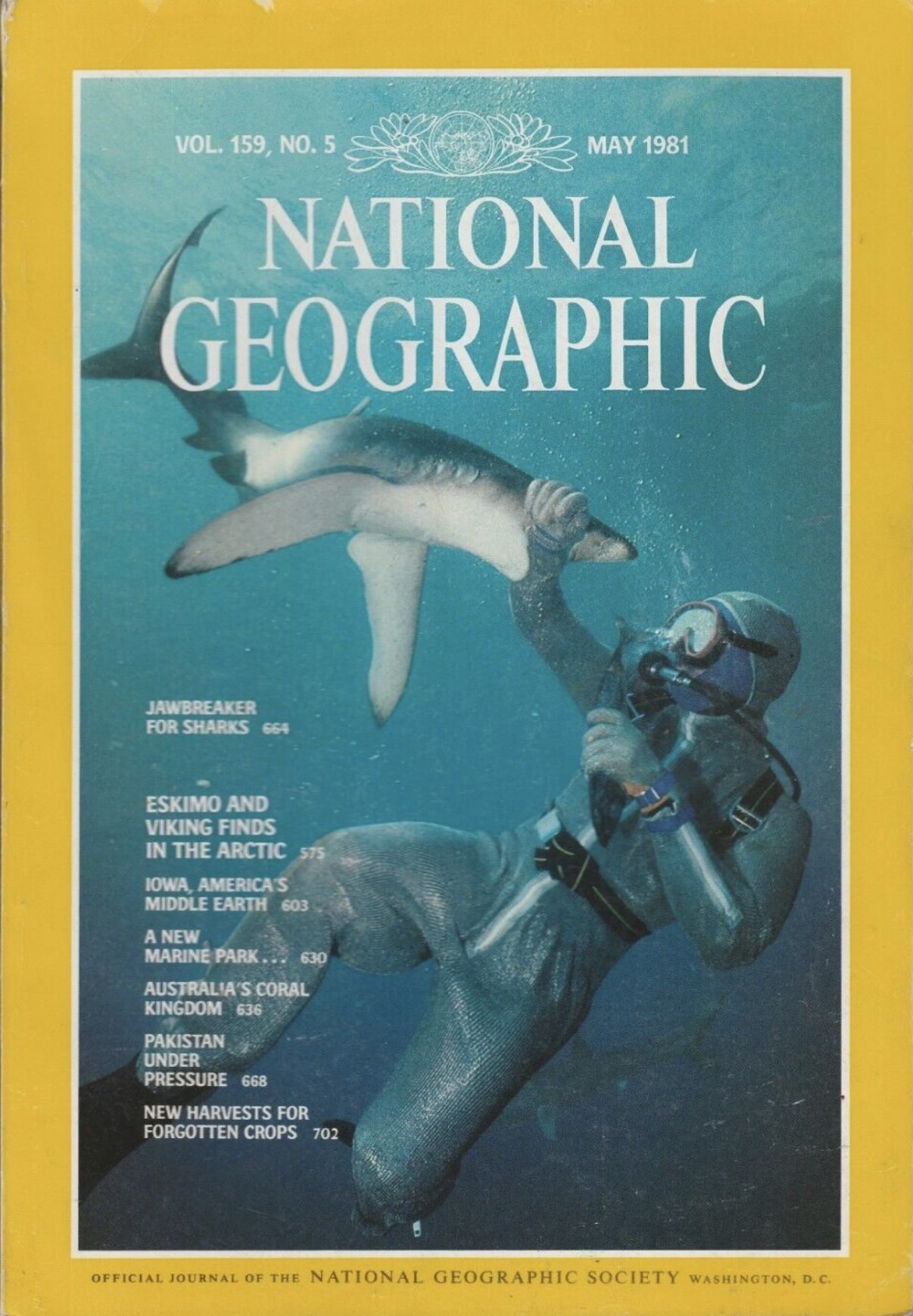

Captured in the National Geographic documentary Playing with sharks, a film directed by Sally Aitken and produced by Bettina Dalton, Valerie’s life could easily have been pulled from the pages of the classic adventure novels she found solace in while hospitalised with polio as a 12-year-old in New Zealand.

“I read Huckleberry Finn and Treasure Island over and over,” she says, attributing her hunger to experience the broad horizons of the wider world to the many hours spent escaping into books as she recovered. “Books opened up all the possibilities on the planet, and nine weeks later I was walking, and my mother came and took me home. They said I couldn’t, and I did.”

This defiance, combined with an incredible affinity for the water, motivated her to follow her dream of diving rather than a more traditional path. Her confidence and comfort in the marine environment earned her titles and respect in the male-dominated world of spearfishing. “I returned to Sydney and joined a club,” Valerie recalls. “It was a very macho sport – there were 13 women and 700 men.”

Described as lethal for her skills beneath the waves, Valerie Heighes – as was her maiden name – had to be stronger, sharper and better to claim her place among the men. “She was a great hunter,” says marine biologist Jeremiah Sullivan in the doco.

“All the great environmentalists start as hunters because they’re the only ones out there who are observing, and learning.”

Valerie only ever killed one shark, a grey nurse – the largest ever killed by a lady skin diver in the world, as the media covered it. “I wish I hadn’t,” she says sombrely. “But at the time, the attitude was that there’s just so much life in the ocean, you could take what you wanted and it wouldn’t even make a difference.”

Through spearfishing, Valerie met the four-time Australian champion and world champion Ron Taylor. Ron shared Valerie’s appetite for adventure, and would take out his 16-millimetre camera to capture the underwater action and plethora of marine life. The bikini-clad Valerie soon caught his eye, and he asked her to model for him, capitalising on the novelty of a daring female in the lead role. “She was interested in the underwater world like I was. She wasn’t wimpish,” Ron said of their attraction.

As a dynamic diving duo, Ron and Valerie married and went on to make a series of underwater films about diving with dangerous underwater animals, including “submarines with teeth”. But the closer the pair became to sharks, the less they were inclined to kill them or any marine life. “We put our spears down and said from now on, we’re shooting them with our camera,” Valerie remembers.

In a workshop in their home in southern Sydney, Ron designed and made his own camera housings. “We did whatever we could to make a living from what we loved to do,” says Valerie. “Ron was a genius – he’s the cleverest man I’ve ever met.”

Ron filmed the fearless Valerie playing peekaboo with seals, caressing sea snakes and handling moray eels, at ease among jellyfish and manta rays. “It was remarkable,” says Sullivan. “Here was this beautiful Australian gal doing all these crazy things that nobody’s supposed to be able to do.”

In the 1960s, the Taylors were among just a handful of people in the world who were shooting documentaries about the ocean. There was Hans Hass, Stan Waterman and Jacques Cousteau, who was funded by the French government and had a huge profile thanks to his popular TV series The undersea world of Jacques Cousteau – and then there was Ron and Valerie with their original and groundbreaking formula. It was the golden age of new underwater information.

Ron and Valerie were diving with great whites as well as other sharks, including the notorious oceanic whitetip shark, which is said to be responsible for more attacks on people than all other species put together. “Very little was known about sharks in those days,” Valerie recounts.

“I remember the first time I saw a great white – it was like a freight train coming out of the mist. It was magnificent.”

Thanks to a tip from a local fisherman, Marion Reef in the middle of the Coral Sea was chosen to find and shoot “good sharks” – the most dramatic for filming – and that’s where Valerie got to know these creatures and understand their intelligence. “A year after our first visit, we returned,’ she says.

“Before we’d even dropped anchor, sharks came up to our tinny – they knew there would be food, and we realised a shark can learn. You can teach them simple tricks very quickly. I knew what would make a good image – I was a photographer.

“I wanted to shoot a shark swimming over some pink coral and knew where the sun was going to set. So I waved around a bit of food and the whitetip came in straight away. I bumped him on the nose and wouldn’t give it to him.

“Eventually, he came in over the pink coral and I gave him the food. I did that twice, and he knew that if he came in over the pink coral, he’d get a piece of food. They learn, and faster than you can teach a dog!”

She often compares sharks to dogs. “It’s like any animal. Once you get to know them and understand them, you have a different attitude toward them altogether. There are all sorts of dogs, and all sorts of sharks.”

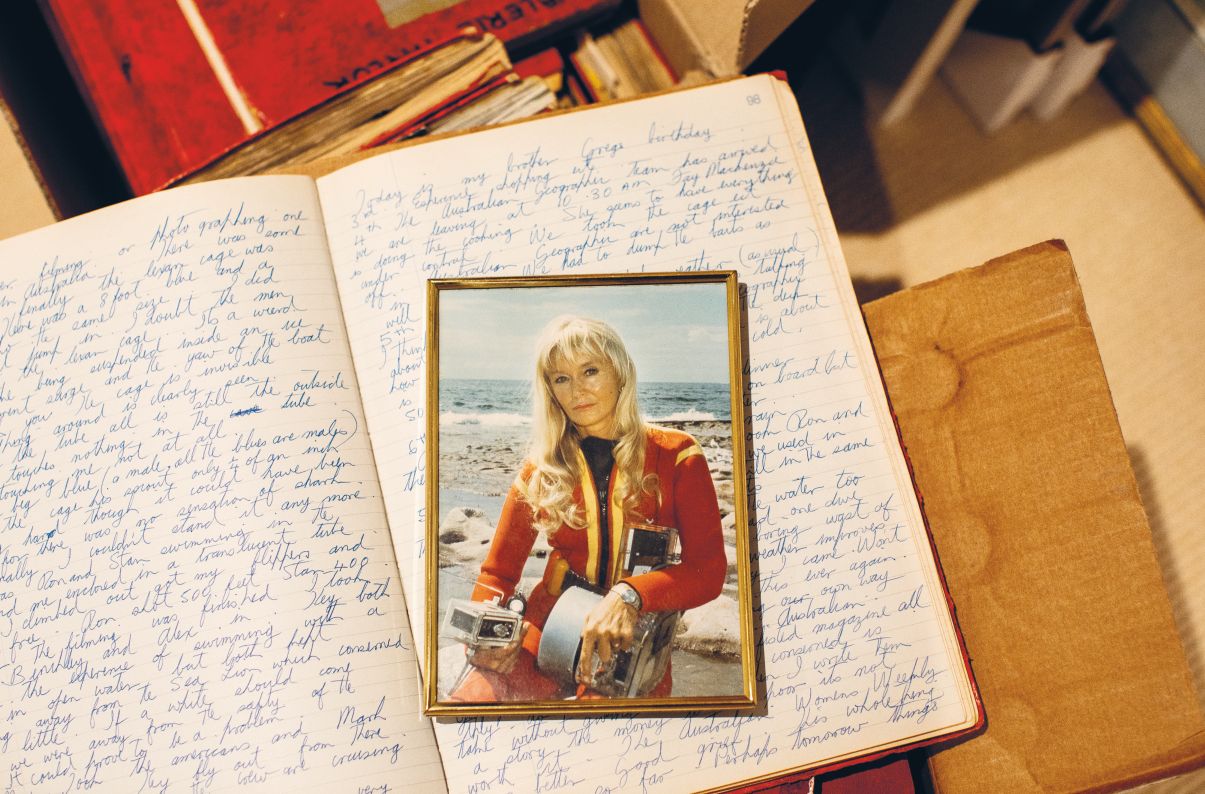

Valerie’s willingness to leap into the water in her trademark pink wetsuit, with her blonde mane flowing, churning out fish guts to attract these mysterious predators, earned her the respect of oceanographers worldwide.

“Valerie had the courage and ability to connect with a species we didn’t know very much about in those days,” says Jean-Michel Cousteau, son of Jacques.

“And she could share that with the public. She helped everyone, including us. Whereas historically, we stayed away from sharks, Valerie was getting close to them and learning about their behaviour.”

But it was the film Blue water, white death in 1969 – the brainchild of American filmmaker and underwater photojournalist Peter Gimbel, who was fascinated with sharks and had seen Rob and Valerie’s films – that would prove the springboard to international acclaim.

“Peter wanted us on board because he knew we could handle these beasts – he gave us the adventure of our lives,” she reflects.

It was the first film of its kind and Valerie, the first female to ever undertake such dangerous adventures, had earned her way on the voyage. Shot at Dangerous Reef in South Australia, the film features a feeding frenzy of Carcharhinus longimanus, the whitetip shark that hunts in packs.

Armed with a stick – while the underwater camera crew had massive gear to fend off the 100 or so huge hunters – Valerie swam among the sharks as they fed on a whale carcass. When they nudged her to see if she was food, she “bumped them back hard,” she says, having observed their interactions with each other.

“We went into a world that existed 20 million years ago and were accepted as other marine animals, but only after we’d made a place for ourselves with the pack.”

The footage of that dive represents the past. It was the 1960s, “the era when a good shark was a dead shark,” as president of Shark Savers and WildAid Wendy Benchley puts it. But what seemed foolhardy was actually collecting evidence to prove sharks are not ruthless killers – they mind their own business. It’s about mutual respect.

Since then, sharks have been hunted based on the fallacy of a dangerous reputation and plundered for their fins. And post-Jaws, the slaughter only increased. “Jaws is a fictional story but the public believed it,” Valerie laments. “It must be some kind of instinctive, subconscious fear of being eaten alive.”

Universal Studios, which backed the film, even paid for Ron and Valerie to tour America and appear on talk shows in an attempt to diffuse the fear frenzy. “Jaws did set things back,” admits Valerie.

“The thing that I regret most is people went out and killed sharks. We became very upset about that, and Peter Benchley said he would never have written the book if he’d known what the aftermath would be. It gave all sharks a bad name – most are totally harmless, like the grey nurse shark.”

Also known as the sand tiger shark or the ragged-tooth shark for its intimidating teeth, the grey nurse was all but wiped out in Florida. Valerie was determined to halt the killing of this misunderstood species: “When I get my teeth stuck into something, I don’t let go!” she says, and she dedicated her energy to lobbying governments until the grey nurse became the first shark to be protected in New South Wales in 1984 and, by 1996, the world.

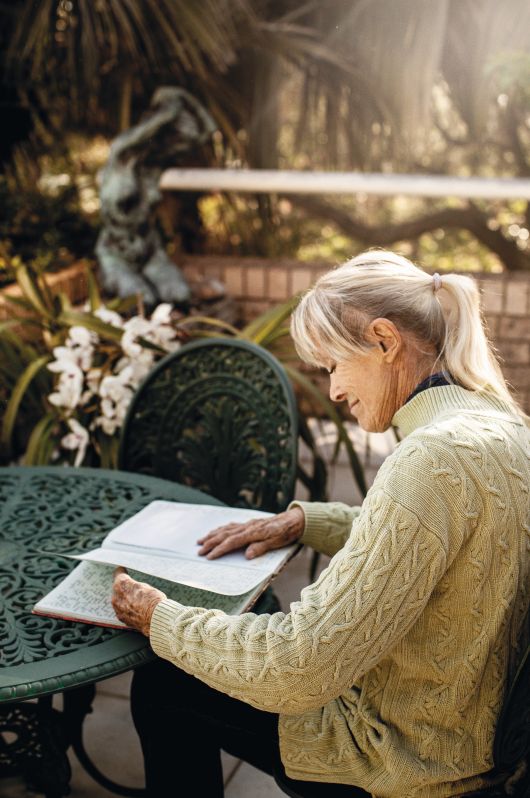

Ron passed away in 2012, and since then, Valerie has continued to use her expertise to ensure the ongoing survival of the grey nurse shark. With the aim of surveying their remaining populations, Valerie is assembling an army of citizen scientists – scuba divers, First Nations leaders, school children, scientists and celebrities – for the initiative. It’s a rallying cry of support for the definitive head count of the sharks, raising awareness of their endangered state.

In the second of four censuses, conducted on 26 August 2023, Valerie’s band of divers surveyed 13 grey nurse shark aggregations on Australia’s east coast to count their population. The first census showed that there were less than 300 – far fewer than the estimated 2,000. As a result, further censuses are now planned to verify the numbers.

Once culled in great numbers, grey nurse sharks can live for 40 years but are slow breeders, giving birth to only two young, and face threats such as habitat degradation and incidental catch by commercial fishing. With the same tenacity that earned her a global following, Valerie is lobbying for Marine Park Area (MPA) protection for 30 known aggregation sites or breeding areas that she refers to as her string of pearls.

A documentary of the same name is in the making. Drawing on the Taylors’ film footage and Valerie’s success in securing protection for the grey nurse shark 40 years ago, it will shine a light on the beauty and significance of this harmless species.

No less, as part of her broader aim and enduring legacy, Valerie has a vision for First Nations people to become the sea rangers and custodians of these sites, managing dive and eco-tourism so that her string of pearls will ensure the ongoing survival of the grey nurse sharks well beyond her lifetime.

At nearly 88, Valerie has lost none of her verve or passion for shark conservation. Older, wiser and even more motivated, clad in her pink wetsuit and with coloured ribbons in her long hair, she is every bit the adventurer and advocate. “Nature made the perfect animal,” she says. “I come out of the water screaming my head off with joy every time. I just love it.”