Out of the BLUE

Ocean talks global marine protection and endangered fish stocks with the Blue Marine Foundation.

Written by Esther Barney

01 February 2018

When the Blue Marine Foundation (BLUE) hit headlines with its educational film The End of the Line a decade ago, most of the public was unaware of the precarious state of the world’s fishing stocks. Through educational campaigns and advocacy, the charity has made significant headway in increasing the amount of marine protected areas around the globe.

Hot on the heels of a spotlight feature on the hugely popular Blue Planet II and significant achievements in both the UK and European Parliaments, BLUE’s Senior Projects Manager Rory Moore tells Ocean why it’s never too late to make an impact and help save the oceans.

Ocean Magazine (OM): When did you first get involved with BLUE and what was your professional background before that?

Rory Moor (RM): I joined BLUE three years ago to work on the Foundation’s international projects. My background was in managing wildlife and conservation research projects overseas. After studying Marine Biology at Plymouth University in the UK, I spent three years in the Maldives before undertaking an 18-month research trip across the Pacific on a sailing boat, diving with whale sharks to try and ascertain how and where they breed, which remains a mystery to us even now. After that, I relocated to Indonesia for my PhD project.

OM: BLUE has a number of projects and areas of activity, from trying to prevent the collapse of global fish stocks to expanding the amount of protected waters. How do you juggle so many diverse projects?

RM: Combatting overfishing is our overall goal. One tool for doing this – perhaps the most effective – is to create marine protected areas. Our target is for 10 per cent of oceans to be protected by 2020 and 30 per cent by 2030.

When you create a marine protected area, the end goal is effective marine conservation; you can’t always close an area completely to fishing and make it a “no-take” zone. If you want to achieve meaningful conservation in parts of the world with extensive local fisheries, such as the Mediterranean or Indian Ocean, you need to ban industrial scale fishing, but develop sustainable fishing practices for local fishing interests.

BLUE is fighting large-scale, unsustainable fishing. Electric pulse fishing in the North Sea is one such example. Fishermen on the east coast of England are reporting widespread destruction of biodiversity due to this indiscriminate fishing method which is even happening in Special Areas of Conservation. Alongside the French NGO Bloom and representatives of small-scale UK fishers, we have been raising awareness of the issue. On 16 January 2018, to our delight, the European Parliament voted strongly in favour of a full ban of electric fishing, but there is still work to be done because the European Commission is now deciding whether to put the ban into practice.

We are supportive of small-scale, sustainable fisheries. We developed a model in Lyme Bay, designed by local fishermen, conservationists and regulators. The result was an effective marine reserve, which supports a sustainable and profitable local fishery, a win-win for conservationists and local fishing communities.

For an organisation as small as BLUE, which was formed almost 10 years ago, we have had a big impact. The recent #BacktheBlueBelt campaign conceived by BLUE, which encouraged members of the public to write to their MPs and ask them to sign a ‘Blue Belt Charter’, has resulted in 265 British MPs from eight political parties signing the charter so far. The level of support for this campaign, which was designed to coincide with the increased interest in oceans arising from the BBC’s screening of Blue Planet II, was hugely encouraging and will help to ensure that the Government’s Blue Belt commitment is upheld.

OM: One of BLUE’s current main missions is to place at least 10 percent of the world’s oceans under protection by 2020. Are you on track?

RM: The consensus figure is somewhere around six percent. We do have a strong chance of hitting our 2020 target and countries with big ocean estates such as France and the UK are making big contributions. The United States was making great strides, but this has stopped under the current regime. The protection of areas around the British Overseas Territories in the Pacific, the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean will make a big contribution. That is why the Blue Belt campaign is so important to BLUE.

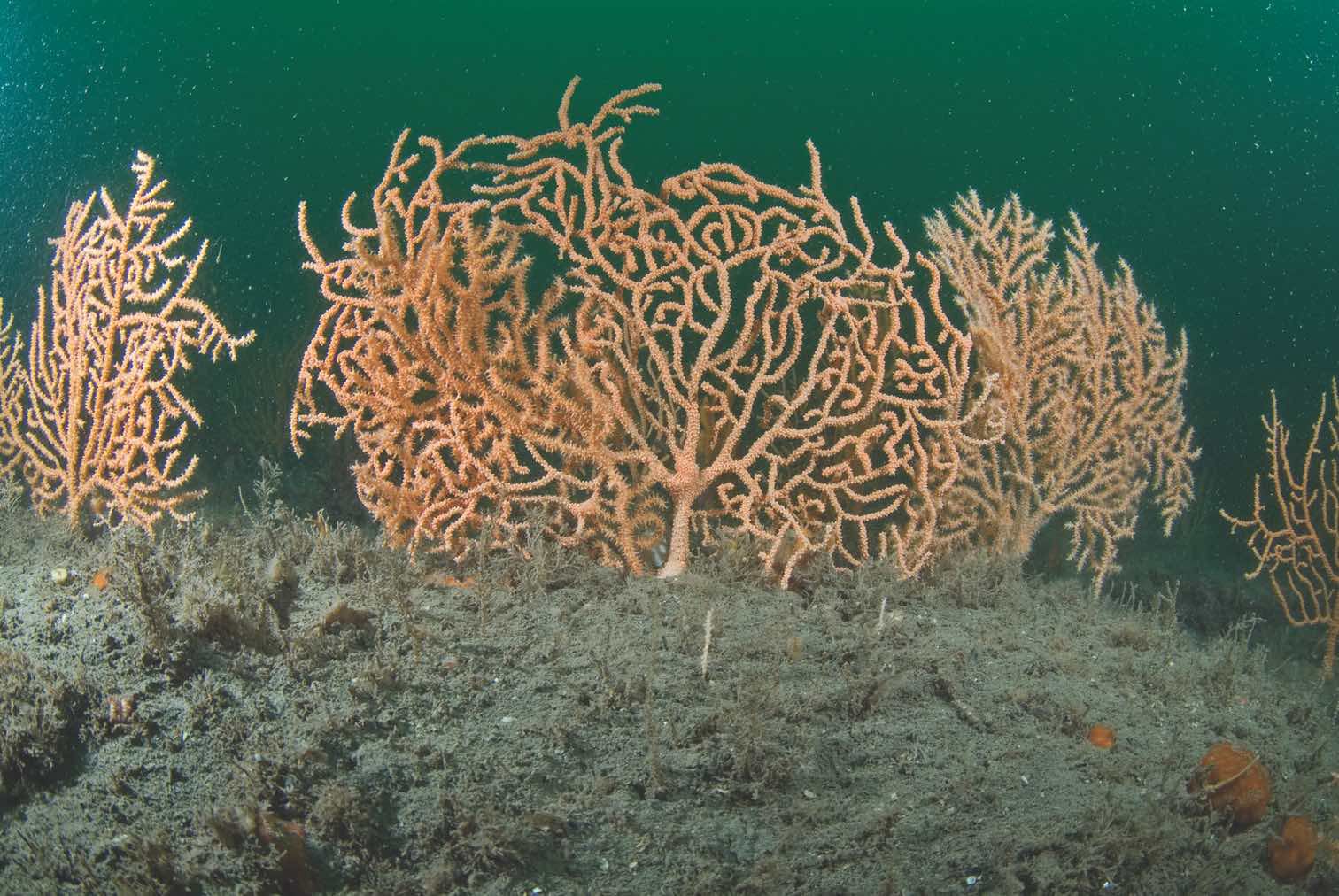

But we believe that marine protection should prioritise areas with high biodiversity and productivity; areas of ocean which support endangered species, breeding sites, migration routes and nurseries for marine life. It’s not just a question of notching up percentage of ocean protected, but of protecting the most vulnerable areas. That’s why we are making a big push to increase protection in the Mediterranean which was one of the most productive seas in the world, but which has been horribly overfished in the last 50 years.

OM: Are there any new projects or campaigns BLUE is involved with that could be interesting to the readers of Ocean?

RM: We think readers of Ocean will be interested in all our projects because this is about restoring the ocean and the incredible life within it for future generations. Readers may be particularly interested in our project in the Maldives, where we are working to restore reef fish stocks and create protected areas to help restore the reefs so they become more resilient to climate change. Healthy reefs support healthy populations of fish and vice versa, so if you can combat overfishing in these areas, you can reduce the impact of climate change.

There has been a lot of discussion about the destruction of the Great Barrier Reef linked to El Niño weather events. These events used to be more infrequent 30 to 50 years ago but they are becoming more regular and more severe every year, changing weather patterns and warming the oceans. Last year alone, 90 per cent of the reefs in the Maldives were bleached as a result of warmer waters and the same thing is causing bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef. Healthy reefs with thriving fish populations are more resilient than fished out reefs, which is something we can help with when it comes to protecting fish populations.

OM: The overfishing crisis is only recently coming into the public consciousness since films like The End of the Line and headlines in newspapers and on television. How can consumers make the best choices with fish when it comes to ordering in restaurants or buying for cooking at home?

RM: The provenance of the fish is the most important thing, so you can identify how it is caught or farmed; organic, sustainably caught and line-caught are terms to look out for.

The Marine Stewardship Council has a map on its website that shows which stocks are labelled as sustainable. Although it’s not completely comprehensive, it is a helpful start. It is best to avoid large fish like tuna or swordfish if you can. We are so fussy when it comes to the kinds of fish we want to eat, such as salmon, tuna, cod. There are much healthier and sustainable choices like pilchards, anchovies and mackerel, which are just as tasty and are packed with nutrients.

When any wild food source becomes scarce, we tend to start farming it to have a more reliable supply. But one of the problems with a lot of farming practices is that you need to put much more energy into rearing the food than you get back when consuming it. Fish are more efficient than terrestrial farmed creatures but you still have to feed a fish more than you get out of it once fully reared. For example, if you have to use three kilos of sardines to rear one kilo of salmon, it makes more sense to eat the sardines and feed three times as many people.

When it comes to fish farming, these issues have to be addressed because over 50 percent of fish that is currently traded is farmed. We need to make the system more sustainable, and a lot of that comes down to what we are feeding the fish. We are putting pressure on stocks of smaller (bait) fish to feed the larger fish. Using waste products from sustainable fisheries to feed the fish is one solution. There is another initiative that uses fly farms to break down waste products from human activities, such as food scraps, and the fly larvae can then be used to feed the farmed fish. This has a twofold benefit: the food scraps are naturally disposed of and the fish eats something it would consume in the wild rather than synthetically produced foods.

OM: If 90 percent of global fish stocks are fully exploited or overexploited, could we be reaching a point of no return when it comes to the health and survival of our oceans and the species within them?

RM: We can recover even severely depleted fish stocks and we have proven this so many times. It is rare that species actually become extinct in the wild but rather that severely overfishing reduces numbers heavily. Fish do move and breed but we are just too good at catching them.

Bluefin tuna stocks in the Mediterranean were down to under 10 per cent of what they had once been and now, after significant efforts to regenerate the populations, they have rebounded to relatively healthy levels, according to ICCAT [the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas]. North Sea cod was almost wiped out but in some well-managed and protected areas, stocks have returned to sustainable levels within in 15 years.

In the early-to-mid 1900s, most species of whales were heavily depleted from industrial-scale whaling but since the ban on whaling in 1986, most populations are rebounding well. They haven’t recovered to the levels of 500 years ago, but they are heading that way because of good management. Fish populations can recover far faster than those of whales, so this is a great indicator for the potential we have to turn the situation around.

OM: Where can readers find The End of the Line to learn more about your work?

RM: An updated version of The End of the Line can be rented at vimeo.com/ondemand/theendoftheline2 or shorter clips can be found on our Vimeo channel here and here.

OM: What can individual yacht owners do to help with BLUE’s mission?

RM: As well as making the right ordering and purchasing choices when eating fish, there are a number of ways you can reduce your impact on the environment through good yachting practices.

The Blue Marine Yacht Club (BYMC) is our club for superyacht owners. Members support the running of the Blue Marine Foundation and in return are invited to exclusive parties, dinners and political events. See our website for more details. But we welcome all donations, however small!

We have the BMYC Code of Conduct with lots of advice, including not dropping your anchor on seagrass beds, which can have a huge impact. Many people are unaware that seagrass beds can trap 35 times more carbon dioxide than the same area of rainforest and they also provide a vital protective habitat for juvenile fish populations. When an anchor chain moves across a seagrass bed, it ploughs it up and destroys it. We advise to use moorings instead, where possible, and we are promoting an initiative in the Mediterranean to create “eco moorings” which help maintain healthy seagrass beds.

We also have our annual London to Monaco cycle ride each September, which raises funds for ocean conservation and, as well as being for a great cause, is a lot of fun! See our website if you fancy the challenge of cycling through eight countries in seven days!